As the illegal war in the Ukraine continues, there is a growing discussion about the need to move away from a reliance on Russian commodities in the energy market, which presents new challenges to energy policy. The timing could hardly be worse, coming as it does during a global gas supply and demand imbalance that has seen gas and electricity prices around the world surge. The reasons for those price dynamics have been covered in previous posts – here I would like to address some of the options now facing policymakers, particularly in the UK.

“You can’t simply close down use of oil and gas overnight even from Russia, that’s not something that every country around the world can do. We can go fast in the UK, other countries can go fast, but there are different dependencies,”

Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland

Predictably, if disappointingly, every special interest lobby imaginable is now claiming that their technology is The Answer. Renewables advocates believe we must rapidly build more renewables, fracking advocates argue we need to immediately lift the moratorium on fracking to achieve energy security, heat pump advocates argue that homes need to immediately remove gas boilers in favour of (guess what!) heat pumps, of course hydrogen proponents believe hydrogen will save the day, and I have even seen technology companies trying to argue that if suppliers had deployed more digitisation they could have avoided the problems that caused so many to fail last year. Most of these arguments are not only deeply self-serving, they have no hope of delivering anything useful over the required timeframe, which is essentially the 8 months before we get into next winter.

People are also conflating various different issues, but most commentators are becoming very concerned about further price rises, with many forecasts for next winter’s retail price cap being at or above £3,000, as well as the impact of high price volatility impacting industry.

What is happening with prices?

Gas and electricity prices have become very volatile and the forward curves have changed shape dramatically. At the beginning of last year, gas prices at the NBP were sitting around 50 p/th. By the beginning of this year they had quadrupled (after a period of even higher prices in December). Now the front month contract on ICE is trading towards 300 p/th, down from 540 p/th on Monday and when within day trading exceeded 800 p/th. I’m finally beginning to agree with Ofgem’s oft-repeated slogan that market conditions are “unexpected and unprecedented” – these types of gyrations are genuinely unusual even in commodities markets.

Looking closer, the forward curve has gone from some backwardation in November, to flat in February, to massively backwardated now as the front of the curve has risen sharply. Trading liquidity looks to be pretty concentrated in the front couple of months, and it is almost certain that only traders with physical positions are currently trading. There have been suggestions that the main gas indices such as the front month TTF contract should see their prices capped, but it is unclear who could do this and on what authority. In equity markets, exchanges can suspend trading when it becomes disordered, but in physically delivered energy futures markets this would disrupt actual physical flows and add to the chaos.

It is interesting to see that EUA prices have collapsed – this is counter-intuitive in some ways since a reduction in the use of gas would suggest an increase in the use of coal in the EU, particularly in electricity generation, but there had been signs that much of last year’s increase was driven by hedge fund money which is almost certainly now taking profits and exiting the market. Even from a fundamental perspective, although demand for EUAs may rise due to gas-to-coal or oil switching, the carbon market is not a real, physical market, it is a market that was invented by politicians. If politicians become concerned that end-user energy costs are too high, they can force down EUA prices or suspend the requirements for companies to submit EUAs for various activities, which would certainly cause a de-valuation.

The same logic can be applied to the nascent UK ETS, although it is not clear that the UK held as much interest for non-physical players as the European emissions market did.

Policy choices for the Government

A month ago, when Ofgem announced a new record level for the price cap, the Government tried to soften the blow with a range of subsidy measures aimed at households. These measures were underpinned by an assumption that high market prices were temporary and that by next winter they would have started to fall. This was a view I held last autumn, but as the winter progressed, analysts began to cast doubts on whether European gas inventories could be restored over the summer, and if not, this would likely defer a meaningful price correction until the following spring. Clearly all bets are now off as a result of the war in Ukraine, and my sense is that even if Russia were to immediately withdraw, apologise and pay reparations, the damage done to its relationships with the rest of Europe will take decades to repair.

European governments have long gambled on Russia avoiding extreme behaviours to allow a somewhat uneasy relationship to be maintained where Europe relied on Russian energy and Russia relied on the money raised by selling its energy to Europe. The invasion of Ukraine has shown that the Russian government is capable of and willing to cross what most people assumed was an un-crossable line, that is the outright full invasion of another sovereign state. There is no going back from this – having crossed this line, European governments will never be able to trust that other lines may not be crossed in the future by the Russian state, and will need to protect themselves accordingly. In the near term, this is leading to a re-militarisation of Eastern Europe, something it is difficult to believe that Russia wants, and in the medium to longer term, this will lead to Europeans seeking to disentangle themselves from Russian energy.

Policy choices: gas

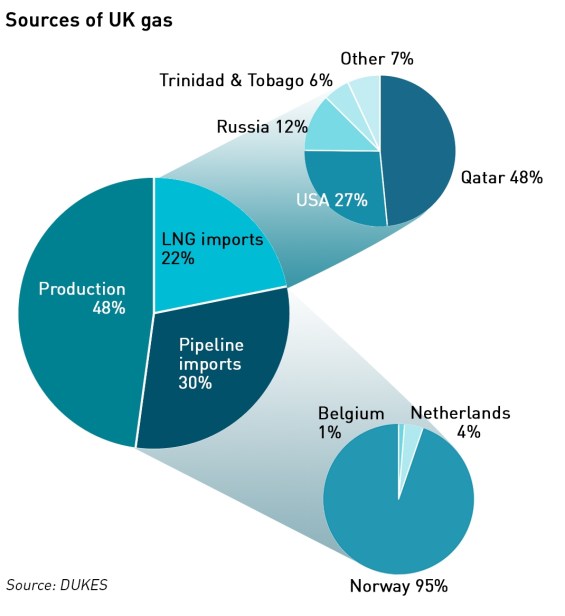

Only about 3-4% of the UK’s gas comes from Russia, and this can be fairly easily substituted with other gas imports albeit at potentially high prices. The vast majority of UK gas comes from the North Sea – either our own production or from Norway. So security of gas supply for the UK is not really under threat, although as a participant in the global gas markets, affordability is a concern. However the UK is not a poor country and can afford to pay what is necessary to ensure that at the national level, gas continues to flow.

Looking to the future, there are signs that the attitude to security of gas supplies is changing and that there is now a greater interest in exploiting domestic gas resources. There is suddenly new pressure to get on with fracking – there is currently a moratorium on fracking, and the two existing wells are due to be permanently sealed.

This would be a mistake – these wells should be further developed and the tolerance level for earth tremors should be raised from the current level of 0.5 on the Richter scale to something closer to 3.0…”earthquakes” of 2.5 – 3.0 occur naturally in the UK fairly regularly, and rarely do more than crack a few plates.

Apparently in the UK we experience a magnitude 4.0 earthquake every two years and a magnitude 5.0 every 10-15 years. The citizens of Groningen in the Netherlands have faced higher seismic activity as their gas field depletes, and are now willing to see production increase regardless of the greater strength and frequency of tremors which had been reaching 2.5 – 3.5 before extraction was reduced.

UK seismic hazard analysis suggests that minor property damage occurs at 6.0, so the controls on seismic activity relating to fracking are demonstrably far too conservative and should be relaxed.

However, fracking is not going to change the gas supply equation for the UK in the next 8 months, and possibly never, since we do not know for certain that there are economically viable shale gas deposits on (under) British soil. A more likely route to success would see an increase in UKCS activity, but again, not really in the next 8 months. The UK does not have any real swing production, so the only way to increase output is to drill more wells. Some projects are more or less ready to go, with field development plans established (if not necessarily approved) and routes to financing (eg through an existing borrowing base facility) available.

So on gas, the sensible policy actions are:

- Negotiate firm long-term LNG supply agreements with limited diversion rights, alongside restrictions on cargo re-loading. This will ensure LNG actually reaches the GB gas network.

- Approve new UKCS E&P activity, and take a pragmatic approach to issuing new licences / approving field development plans.

- Remove the moratorium on fracking and raise the tremor limit to 2.0 or 2.5.

- Evaluate new seasonal gas storage investments, either bringing Rough back to use, or developing another depleted/near depleted gas field, possibly one of the sites identified for carbon storage.

Of these, only option 1 would have an impact this year.

Policy choices: electricity

The picture on electricity is much more difficult as winter capacity margins are falling to worrying lows. This year’s T-1 auction for delivery next winter saw a shortfall for the first time, procuring 365 MW less than the target. As about a third of the assets that secured contracts have not yet been built, there is some delivery risk. The condition of the nuclear fleet is worrying, particularly as NG ESO has been using the average availability over the past 3 years in its Winter Outlook calculations, which is not prudent for end-of-life assets.

I have read calls for the nuclear closures to be halted, but this is to mis-understand the drivers of these closures in Britain. Unlike Germany and Belgium, British nuclear power stations are closing for safety reasons rather than political or environmental reasons, and therefore the closure plans cannot be delayed or reversed.

What can be done is to halt and potentially reverse the closures of the remaining coal power stations, at least until Hinkley Point C opens. In the near term, allowing the remaining plant to run without restrictions (ie free from environmental limits on running hours) would reduce the need for gas, which would be helpful at the margin. The incremental environmental harms can be discounted – on a global basis running a few GW of coal power for a bit longer in Britain will have a minimal impact. Of course the currently mothballed Calon CCGTs should also be brought back into use to support capacity margins next winter – the fastest way to strengthen these margins is by not closing currently running plant, and by re-opening assets which already exist, before building anything new.

The only other lever for improving capacity margins over such a time frame is a public campaign to reduce consumption. This has already started, with people being encouraged to turn down their thermostats by 1 oC. Astonishingly, the average indoor temperature in European buildings is 22oC! For most people, this is much higher than should be necessary for comfort, assuming a sensible, seasonally appropriate level of clothing is worn – turning up the heating and then sitting around in T-shirts / bare feet should be strongly discouraged and made socially unacceptable in the same way drink driving is widely considered objectionable.

“The average temperature for buildings’ heating across the EU at present is above 22°C. Adjusting the thermostat for buildings heating would deliver immediate annual energy savings of around 10 bcm for each degree of reduction while also bringing down energy bills,”

– International Energy Agency

On top of this, there should be efforts, led by local councils to support people in fuel poverty, partly through advice, to ensure they understand how their heating systems work and how to use them efficiently, and also to support them with basic repairs such as fixing broken or badly fitting windows and doors, which are cheap and can immediately reduce heat waste. Since even cheap actions are unaffordable for those in fuel poverty, these repairs should be paid for through public funding.

Longer-term, we need to get a grip on heat losses in homes. So far the energy transition has focused almost entirely on subsidising renewables – this is easy to do and can show rapid progress, but we are reaching a saturation point beyond which new investments lose efficiency without other supporting investments and reforms, particularly in networks. Subsidy schemes have been poorly designed, and multiple reports have found that consumers are over-paying for the renewables built to date. Yet these legacy subsidies will continue to burden consumers for decades, irrespective of any new schemes or auction rounds – payments for the defunct Renewables Obligation scheme are set to continue until 2037.

Not only should these costs be moved from bills to general taxation, but there should be a moratorium on new renewables subsidies with the focus shifting to a major publicly funded retrofit effort to reduce heat losses in homes, particularly in social housing. This is a difficult challenge, but it is vital if the energy transition is to succeed – current concerns about affordability should provide the impetus to finally set aside the easy but expensive subsidisation of renewables, and deal with energy waste in homes.

So the policy actions on electricity should be:

- Delay coal closures and re-open the mothballed Calon plants.

- Advise and assist consumers on short-term demand reduction.

- Suspend VAT on domestic energy bills, move green levies to general taxation, and provide domestic consumers with a direct energy subsidy for next winter (replacing the previously announced loan).

- Apply a windfall tax to renewable generators that receive the Renewables Obligation and do not have a fixed price PPA.

- Approve new large-scale nuclear that can be built faster than the troubled EPR (ie ABWR).

- Pause new renewables subsidies and establish a clear plan for addressing heat losses in homes, with defined targets, alongside a reformed EPC which takes account of the condition and quality of building materials.

There are few real options for policymakers that will relieve market concerns over security of supply and reduce prices. They need to take those actions that can have an impact within months, and then they need to support consumers with high prices. This is hard – the war is raising prices across many sectors of the economy, not just energy – food prices are also rising, and there is a very real risk of a recession. But this makes addressing demand even more important. Short-term actions such as paying for basic repairs could be funded through a windfall tax on renewable generators who have been earning excess profits under the Renewables Obligation subsidy scheme.

It is not hyperbole to say that current energy policy needs to focus on the preservation of life: excluding Russia from the energy markets will preserve life by removing a source of funding for its illegal war; addressing security of supply and affordability preserve life because interruptions to supply and self-disconnection on the basis of cost are both a threat to life, particularly in winter.

Hard to disagree with most of this and one can only hope for some resultant action. However the comments regarding consumer behaviour are ill advised and border-line condescending. Advice on how their heating systems work – really? Approved dress codes to ensure security of supply – really?

I can assure you that when the bills start coming through the letterbox shortly, some will be self-rationing in a frenzy without the need for nanny state politics to rear its ugly head. And others will expect this country to supply one of the basics of modern society without having to reach for the extra jumper, turn off all TVs on standby, or alter their thermostat to a socially acceptable level.

Unfortunately many people do not use their thermostats correctly and don’t really understand how they work., so this isn’t intended to be partonising – it reflects both my own observations and those of industry colleagues. Often people then turn off their heating altogether because they are afraid of how expensive it might be. Sadly for many people, heating is unaffordable irrespective of how they would use it, but there are others for whom some advice around how to use their heating effectively can make a significant difference. It’s worth remembering that due to challenges with literacy, numeracy, digital exclusion, disability and so on, there are people for whom “just Google it” isn’t an option, but leaflets or adverts on television could make a real difference.

Also, it’s not a case of dress codes, but that it’s better to wear weather-appropriate clothing than to use more heating. This is really directed more at affluent consumers, who can afford to spend more on heating – in normal circumstances I would say that’s up to them, although it isn’t particularly environmentally responsible. However if there are concerns over security of supply, profligacy has a wider impact and should be discouraged. Again, there is a surprising degree of ignorance about it: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/02/28/covid-toes-may-nothing-chilblains/.

With regard to improving home insulation, I suspect that most low-hanging fruit has already been taken.

From my own surveying experience, I would suggest that most domestic lofts have been insulated with mineral wool. Admittedly some could be topped up with extra layers, but most people use their lofts for storing light but bulky items, and additional insulation might not be feasible.

Many post 1919 houses with cavity walls have had them filled, though this method is not always adviseable, depending on the degree of exposure and condition of the wall itself.

Finally, how many older homes still retain their original timber windows? Most seem to have been replace with double-glazed uPVC units.

Beyond these relatively inexpensive fixes, we move into external/internal wall insulation and re-laying floor etc, which is a differnet ball-game financially.

We need to accept that the bulk of our older housing stock was brick-built in the era of cheap- and readily-available coal for heating and will never be easy to retro-fit to expensive electric heating, whether by ASHPs or resistance heating.

This is true, although it may not have been done well, and there is currently no penalty for poorly executed work under the EPC. However, carrying out thermal imaging testing can indicate for any given property, where the major sources of heat losses are so they can be tackled. The reason this isn’t being done at scale is because the easy wins have already been made, but heat losses are still high and buildings need to be improved, possibly with each home having its own, different work plan.

The research mentioned in this post gives some idea of what the most useful actions might be, but measurement is key:

https://watt-logic.com/2017/05/08/building-energy-efficiency/

I’ve seen no suggestion that domestic renewables should recive a higher per kW generated price. It used to be that the received price was about 6p/kWhr from solar panels when Eon were selling at 12p. If they are to be selling at 50p,the price paid should be at least 25p. No subsidy required and a great incentive for more people to install solar panels. The real market should decide.

Domestic solar isn’t entitled to new subsidies, and those that can afford it and have space (not every roof is suitable) should consider it. From a security of supply perspective it doesn’t really add very much since the sun sets before the winter evening peak.

On a practical note relating to the nation’s ability to react *before this coming winter* (notably with home improvement / demand destruction measures), there is currently an acute shortage of skilled labour needed to undertake these works, and imports are being significantly hampered by new customs procedures. This is affecting the whole spectrum from large-scale renewables deployment to residential installs, and is being compounded by the DNO connections teams (who have to approve connections) being underresourced and exceptionally slow. A historic lack of investment has led to distribution and transmission networks becoming highly constrained meaning that they are now incapable of accepting new loads or generation without reinforcements that the operators are simply incapable of implementing quickly. We are therefore quite pessimistic about the prospects of any meaningful rapid response before this coming winter.

Interesting post… however I am struggling to understand why you think a windfall tax is OK for the UK renewable energy generators but not for UK domestic gas and oil producers…both have enjoyed high sale prices without significantly increasing production costs…

Because we need upstreal oil & gas producers to reinvest in new UKCS schemes, and current high profits come after years of low returns in the region. Renewables generators with an RO are receiving very generous subsidies (which were criticised by the NAO and PAC) and any reinvestments by them at scale are also entitled to subsidies. These companies are earning excess returns on subsidised assets, so I think it’s entirely fair to claw some of that back.

Thankyou… although I think you are being overly generous in your view that the UK domestic gas consumer needs to support prior over investment by North Sea Producers…

Couldn’t agree more with the “home energy efficiency plan”. Central government should be mandating local government to take care of ‘it’. Local government can think very long-term and build up teams and experts to get the (massive) job done well for their local housing stock. This doesn’t mean no private contractor work , only that the final responsibility lies with the local council. When it comes to finance I think a rise in Council Tax is a better option than central government funding, as the local Council are doing the work and taking the risk they should also get the reward (plus central funding can be pulled…) Equally important is what expectation the resident can expect for the new money raised. For the money they collect , councils should be required to fulfill a ‘minimum’ heating requirement for all homes (a council tax rebate of sorts). There can be a discussion on what ‘minimum’ heat levels actually are, and maybe this is a discussion that has to happen anyway and is probably dependent on the resident. If residents want more heat above the minimum then they pay for it personally.

So, councils take money and pay the bill for a minimum level of heating (or perhaps better phrased as ‘comfort’) for the resident. The trick of this mechanism is that local councils are incentivised to troubleshoot and repair poorly performing homes, because over the decades the investment spent in fixing it is recovered in savings in the councils part of the heating bill. This saving is then pure cash return which they can feedback into fixing even more homes (positive feedback loop). There is a stick too in this mechanism; if councils spend money in improvements that don’t actually work then they’ve spent money for nothing but they still have an obligation to fulfill and nothing to show for it (except angry residents). This will incentivise really accurate house energy measurements and give building inspectors and energy surveyors some teeth, because the person who suffers when a poor job is done is the councils wallet. Poor councils that do a bad job will stick out quickly compared to their neighbours.

There are many soft advantages too; people will complain when they don’t think the council is giving them enough money to cover the minimum ‘comfort’ promised thereby telling the council where the problem houses are; people will become aware of what is the ‘minimum’ and normal amount of ‘comfort’ and make lifestyle changes; the poorest don’t pay council tax and so won’t be burdened; vulnerable people won’t turn off the heating completely because they know that local Government is paying for at least some of it; the NHS will receive less people with illness due to cold; it’s automatic as far as the resident is concerned they don’t have to do anything except let the council do their thing; its hard for a resident to ‘game’ energy benefits as the home is an object that can be measured and monitored (periodically) precisely; residents can ‘opt out’ (that is opt out of receipt of the benefit but they still pay the rise in council tax) so they can still have autonomy from the nanny state; councils may build fewer detached single family home surburbia developments and instead build mixed-use dense blocks of homes ready for heat networks.

Politically a possible approach is through some sort of expansion of the idea of the Winter Heating Allowance , but spread to everybody and recovered through Council Tax. Highlight human rights not to be cold, benefits to the NHS in freeing up GPs or beds and in general so they can get on with more important work, social justice in the wealthy providing for the poorest (but everyone does get something back…), education of the masses about the importance of energy reduction and security in this era of ‘energy poverty’ as we come off fossil fuels etc. It is a radical idea, but these are difficult times, and the “other options are worse”.

Overall, I can’t see decarbonisation of heat actually working without a mechanism like the above that centralises responsibility for action. We need mass surveying and improvements in homes and buildings, heat networks, hydrogen networks, and ‘heat as a service’ models for heat pumps, all of which need economies of scale. Can’t see the private sector managing it but it has to be done so it will have to be (local) government that does it.

Thank you to anyone who read this.;-)

I think the problem with using Council Tax is one of population density and proportinality….many low quality homes can be located in poorer areas, so the burden would fall disportortionately on those who need support in the first place, while more affluent areas would pay less. Also, in your minimum comfort model, coucnils in the north would face higher costs than those in the south. Finally, I think there is a mismatch between what can reasonably be raised through Council Tax and the likely costs of these home improvements (and may even need legislation since councils don’t have unlimited powers to raise taxes).

I support a local-centric approach to this problem for delivery, but I think the funding needs to be socialised across the country as a whole to ensure the scheme is fair.

https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IUK-090322-AcceleratingNetZeroDelivery-UnlockingBenefitsClimateActionUKCityRegions.pdf

Report above from Innovate and PwC also suggest that a ‘local approach’ makes more sense. It’s a bit childish in its design (or at least it thinks its readers are anyway)

I understand your concerns about council tax and the definition of ‘comfort’ but don’t feel they can’t be mitigated. In fact in many ways one is the answer to the other. If the council can’t raise as much funds then they might have to reduce their definition of ‘comfort’. People might demand more from more affluent councils. If this makes people squeamish on a council to council level transfer of skills and resources might even things out.

Any local tax however is a better choice than central funding. The report above has an awful finance model which is a mixture of private finance, central to local government loans and central government grants which are “time bound”. This is a receipe for failure in my opinion. There is not enough profit in it for private investment to spontaneously form an industry, and not enough ‘green’ investment to go around and anyway the risk of total failure is high. Central to local government loans mean debt for local government but where building owners make the gains. “Time-bound” funding means funding that might disappear anytime which is a problem for staff retention and accountability (if the energy team at the council could lose their jobs next year, what do they care if the building isn’t as good as it should be).

If the council raise the tax directly, then they can reap the benefits of getting energy saving right. They can get the right team and keep them, they might even with a track record of success be able to get private finance themselves. Central government can help with research but councils need to build this ability sustainably.

Apart from your views on Fracking I agree with everything in your excellent post.

A planned economy (including a properly engineered energy policy) went out of favour after the fall of the Soviet Union. Market solutions and world markets then dominated. An exciting world with many business opportunities. We have even become confident enough in this model to consider importing our food to be a sound economic approach. Perhaps once again Russia will change our way of thinking.

Markets are calmer when they see a well thought out plan being executed. For example, oil prices were extremely volatile and high following Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, but they dropped 50% literally overnight (Brent traded at $33/bbl at about 1 a.m., and at $17/bbl at 9 a.m.) once the fighting in Desert Storm got underway. So we need a convincing plan to calm markets, even if it can’t be implemented instantaneously. The government and EU plans for windmills and prayer and rationing do not cut it, and Putin knows that.

We need to show that we are serious about alternative supply by canning the Carney ESG rules that starve oil, gas and coal projects of funding. At the global level there will be projects that can be accelerated and pipelines that can enable exports, even if our own projects need more time to fruition. We need to suspend emissions targets and let markets work better to establish cheapest supply. That means encouraging coal and nuclear use where it can free up gas anywhere in the world that can do so. The US could certainly increase coal mining and export quite quickly for example. Diplomatic effort required.

The 1973 oil crisis spawned the International Energy Agency, which was set up to establish stock holding targets for member nations, and also mechanisms to share oil supply in the face of Arab embargoes. Today the IEA is just another international green quango. If it has a purpose it should be to get back to endorsing sensible policy. In reality, its oil sharing scheme was never implemented, and suffered from all the shortcomings you might expect of a centrally planned operation (I took part in test exercises and reported my conclusions). The stock obligations were never released to ameliorate crises, and in any case the separate US SPR releases have not had much effect on markets when they have been mandated.

It may be tempting to think that negotiating destination restricted LNG term contracts is a panacea. In reality, logistic optimisation of LNG supply is crucial to maintaining it. Last autumn we saw huge daily charter rates when inefficient trading patterns led to a shortage of tonnage. Ships were passing each other in opposite directions fully laden in the Med, with shipping tied up in unnecessarily long haul voyages and ballast legs. Finding ways to trade around destination restrictions is key. It was Russian LNG headed for China while Qatari LNG came to Europe that caused prices to soar in destination markets. The unpleasant corollary is that while the Russians are exporting it pays to latch onto the shorter haul supply. For China, bankrupting the West with expensive energy is probably in their interest, even if they pay fancy prices for their own supply, as it simply makes their coal based economy even more competitive.

Greens argue that producing our own gas does nothing to lower prices. That is wrong. If our own supply supplants a long haul source it means we no longer have to pay the extra shipping cost, and the marginal price setting supply is cheaper, and global logistics are less taut. We are currently getting supply from Melchorita, Peru via the Panama Canal, which is obviously rather more costly than from say Trinidad or the US Gulf. Indeed, ships were being heavily delayed to get through the canal, adding enormously to cost and reducing effective supply. Of course, were we to return to self suffiency we would be largely insulated from world markets, just as the US is today.

The real key to LNG supply is ownership. If you own an availability you can trade into a more convenient one for your market. We have been shooting ourselves in both feet by discouraging ownership by Western oil and gas companies. If you leave it to the Chinese and Russians you will pay a fancy price to buy product.

I think the issue with LNG for the GB market is that very little if any is under firm, non-divertable contracts. I wouldn’t suggest that all our LNG should be procured that way, but it seems sensible that we would have at least some firm contracts in the portfolio.

I don’t know how many term contracts UK suppliers have signed. There are more than you might think already. Certainly supply in exchange for a share in South Hook from Qatar, Petronas with a similar deal at Dragon, and BG’s deal with Chenière priced at Henry Hub plus 15% plus $2.25/MMBtu FOB Sabine Point which underwrote the LNG facilities originally. There have been a lot of vessels ex Sabine Point recently. However, we’ve had whole years with none at all when the premium market was JKM. In practice Petronas volumes all stay in Asia, swapped out for other availability to feed Dragon.

Fungibility on destination is essential to make these deals work. Not sure how many more we really need. It’s been notable that Shell have used their Melchorita volumes to supply the UK in recent months too.

Mouseover chart of imports by origin for LNG and pipeline:

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/W0qOT/3/

Map of global gas trade

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/UKsWW/1/

On fracking I would argue that the regulations for seismicity should be the same as for geothermal, which permits up to ML 4. Here’s the recorded seismicity from the United Downs project that was unhindered by the shale gas regime

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/P5OE0/4/

At the moment gas markets are not supportive of storage. The highly backwardness price structures we were seeing earlier in fact support emptying out storage and buying forward delivery supply rather than trying to hang on to gas in store. Of course, that is what you might expect seasonally. But the lack of any interseasonal price variation means that there is no margin in storage. Again, perhaps what you might expect when the EU bureaucrats set storage targets with no regard as to how they can be fulfilled. Storage fill adds to demand, which only serves to push prices higher. There are round trip energy losses from the use of storage as well, and cushion gas to be financed if it isn’t already in place as it was in Rough.

The UK used to cope with seasonality in demand by flexing North Sea production. As we started to depend on imports, that seasonal element transferred to import volumes, only modestly supplemented by Rough. When Rough started leaking and its capacity was cut back the margins remained insufficient to justify its repair. The reality is we use LNG imports to handle demand peaks. Only if our winter import capacity became inadequate would it make sense to add storage: we would see seasonal forward price structures that reflected the economics.

Rough storage at 40TWh was only around 5% of annual demand, and had a maximum redelivery rate of about 10% of daily peak demand. That is outshone by LNG terminal send out rates.

Observing the flow of LNG shipping in recent months I have noted there have often been several vessels sailing in circles in the SW approaches awaiting an opportunity to discharge at Milford Haven. These have built up particularly when we have had milder spells of weather, and perhaps the tankage at South Hook (2 berths, 5 tanks) and Dragon (1 berth, 2 tanks) has not been able to accommodate their cargoes. Of course the floating storage pipeline has been expanded by other vessels en route. Some vessels have had to wait a week to discharge: they may have travelled speculatively, and then not found it quite so easy to secure a buyer for the cargo. There have been times when all three berths have been occupied. Oddly there has been relatively little use of Grain.

The pipelines from Bacton to Zeebrugge and Balgzand have effectively been used as access to offshore storage, exporting when demand has fallen lower, and importing when colder weather increases demand. In fact the UK has been acting to some extent as an offshore LNG terminal for the Continent, which offers the security of supply benefit of landing the gas in the UK first. See the charts here.

https://mip-prd-web.azurewebsites.net/DailySummaryReport#dvDemandTable

I agree with your comments on storage which is my I recommend evaluating new storage rather than just going ahead with it. The question is whether there is a case for a strategic gas reserve – I agree the commercial economics remain difficult, although the timeframe for developing more storage is longer than the current market liquidity, so valuation would be based on a fundamental analysis of supply and demand balances rather than current curves, which are pretty distorted at the moment.

Part of the analysis I would do would be to look at the extent to which the investments required to keep Rough open would have paid off or not given subsequent market developments. My suspicion is that they wouldn’t, but quiate a lot of people have been latching on to this, so I think it makes sense to run the numbers and make the results public.

“…focus shifting to a major publicly funded retrofit effort to reduce heat losses in homes, particularly in social housing”

I was a member of Sheffield City Council in the ’00s, when we had a nationally funded program of refurbishing all our social housing stock, including retrofitting insulation and improving energy efficiency. WE’VE ALREADY DONE IT! This was a major Labour Government push to do this, how on earth are there ANY social housing left that still need improved insulation and energy efficiency improvements?

Articles such as this one suggest otherwise:

https://www.housing.org.uk/news-and-blogs/blogs/colin-farrell/epc-challenge/

I don’t like the EPC methodology, but at the moment it’s all we have. My house has an EPC rating of F (dropping from a D because we replaced some of the gas heating with electric heating), but it’s actually a very cosy house with low heat losses. But the evidence doesn’t really support the assetion that social housing doesn’t need any more improving.

I think you are spot on with your electricity recommendations. The capacity issue will be biting us in the posterior big time. The idea that two hour duration batteries contribute meaningfully to capacity is frankly fraudulent when you start having large amounts of wholly unreliable wind dominating the grid. The wind also crowds out baseload supply, forcing the use of more gas as the flexible balancing resource. We need a capacity market restricted to capacity that can provide sustained output over weeks separate from a peak lopping market, and intermittents need to submit to a Dieter Helm style regime that forces them to recognise the costs of intermittency and inconvenient location.

I’m not entirely in agreement over the rush to cancel Russian supply before we have anything else to compete or replace it. Sanctions mean that the Russians are unable to spend dollars and euros until sanctions are removed. It acts as a rising bribe to behave better, and doesn’t actually fund the war. It’s control over what is exported to them that us more important, although there is little that might be regarded as strategic. For so long as the Russians are prepared to maintain supply the West should take it, while not being complacent about the respite it offers by not pursuing alternative supply.

To tell the truth, it is so wonderful that you covered this topic because there is a lot of ambiguity regarding the future of the energy market and energy policy. I think that we can make different predictions because the situation is really controversial, but I really hope that the majority of countries will be able to find an alternative to Russian gas. It is truly cool that only about 3-4% of the UK’s gas comes from Russia because it indicates the fact that the UK is not so dependent on Russia in this respect and that it increases the UK’s chances to come out on top in this situation. Of course, refusal from Russian gas and transfer to another can significantly affect the financial component of the UK, but it is not such a global problem as an opportunity to stay without gas supplies. I think that if the UK has a great deal of financial resources and can show Russia its independence regarding gas supplies, it will be a great step forward for the UK and it will help take this country to the next level.