Last week the Government published its Net Zero strategy, building on last year’s 10-point plan, with some laudable aims to make the UK a world-leader in the “Green Industrial Revolution”. But, as always, the devil is in the detail, and in this respect the “strategy” is sadly lacking.

“For years, going green was inextricably bound up with a sense that we have to sacrifice the things we love. But this strategy shows how we can build back greener, without so much as a hair shirt in sight. In 2050, we will still be driving cars, flying planes and heating our homes, but our cars will be electric gliding silently around our cities, our planes will be zero emission allowing us to fly guilt-free, and our homes will be heated by cheap reliable power drawn from the winds of the North Sea. And everywhere you look, in every part of our United Kingdom, there will be jobs. Good jobs, green jobs, well-paid jobs, levelling up our country while squashing down our carbon emissions,”

– Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland

Reading this, I’m tempted to add the words “Once upon a time…” because there is an element of fantasy to this utopian view of energy policy, particularly when getting this wrong will lead to energy insecurity, reductions on personal mobility, greater social inequalities and even more excess deaths resulting from under-heated homes.

What are the key elements of the Net Zero Strategy?

Four key principles underpin the Strategy:

- Working with the grain of consumer choice: no one will be required to rip out their existing boiler or scrap their current car;

- Ensuring the biggest polluters pay the most for the transition through fair carbon pricing;

- Ensuring that the most vulnerable are protected through Government support in the form of energy bill discounts, energy efficiency upgrades, and more;

- Working with businesses to deliver deep cost reductions in low carbon technology to bring down costs for consumers and deliver benefits for businesses.

It is disappointing to see an ongoing commitment to the flawed “polluter pays” philosophy, a deeply regressive approach which harms the most vulnerable consumers, while also signalling a continuation of the hugely dysfunctional method of recovering the costs of re-carbonisation through energy bills.

The ambitions for the power sector are full of caveats and lacking in detail

The key objectives of the Net Zero Strategy for the power sector focus on a major build-out of off-shore wind with the aim to make the power sector fully de-carbonised by 2035.

The key objectives of the Net Zero Strategy for the power sector focus on a major build-out of off-shore wind with the aim to make the power sector fully de-carbonised by 2035.

“A low-cost, net zero consistent electricity system is most likely to be composed predominantly of wind and solar generation, whether in 2035 or 2050. To ensure the system is reliable, intermittent renewables need to be complemented by known technologies such as nuclear and power CCUS, and flexible technologies such as interconnectors, electricity storage, and demand-side response,”

– Net Zero Strategy

The ambition to de-carbonise the electricity system by 2035 comes with a huge caveat: “subject to security of supply”. It is highly unlikely that this ambition can be achieved, and the caveat suggests that the Government is actually aware of this fact.

This looks like political flag-waving ahead of COP26 and has little real meaning. Indeed there is very little concrete detail in this plan for the electricity system beyond the deployment of 40 GW of off-shore wind by 2030, up from 10.5 GW today. This is not a new target, and indeed, is not necessarily an appropriate target – recent events have indicated the vulnerability of the GB electricity system to low wind conditions, which cannot be solved by building more wind capacity, and without long-duration storage and reliable baseload generation, risks adding to existing problems.

Much of the rest, including essential aims to enable the integration of renewables to promote security of supply are described in terms of ambitions but fail to set out how these ambitions will be realised.

Power CCUS is not a “known technology” and has so far proved to be an expensive failure

Power CCUS cannot really be described as a “known technology” – to date there have only been four carbon-capture power plants, two of which have closed (the Kemper plant in Mississippi, USA which has been partially demolished recently, and the Petra Nova plant in Texas, USA which has been mothballed since May 2020 due to its poor economics). Of the remaining, two, Boundary Dam in Canada, has failed to meet expected capture rates, and much of the carbon it has captured has been used for enhanced oil recovery rather than being sequestered, and Edwardsport in Indiana, USA has suffered from low reliability and huge cost over-runs.

So far CCS has failed to live up to its promise, as described very well in this article, and where large CCS projects have got off the ground they rely on hydrocarbon fuel production or processing for their economics. There is a long way to go before power CCS can be considered viable, despite years of effort and US $ billions of investment worldwide.

Long-duration storage will be essential to balance a net zero electricity system

Storage, in particular long-duration storage will be essential to balance a net-zero electricity system. The details of the Government’s plans for storage are contained in the Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan where it recognises the challenges around long-duration storage which, with the exception of pumped hydro, is characterised by novel technologies which have yet to be demonstrated at scale or commercialised. To address this, the Government has launched a “major competition” with up to £68 million of funding to accelerate the commercialisation of first-of-a-kind longer duration energy storage. Significantly more than £68 million is going to be needed to get long-duration storage into the market.

While flexibility in the electricity system will be important, load shifting can only achieve so much. Last winter we had 12 consecutive days with almost no wind output – it simply wasn’t windy – and no amount of load shifting can manage that deficit, particularly in an electricity system dominated by wind power. Without a reliable form of low carbon baseload electricity (see the problems with nuclear below), long-duration storage will be essential if the electricity system is to be de-carbonised. The GB market currently has 3 GW of pumped hydro and 1 GW of chemical battery storage.

There is limited scope for more pumped hydro given geological constraints, and current chemical batteries have a duration of a maximum of 4 hours, with the average being about an hour and a half. That 1 GW of chemical batteries provides around 1.5 GWh of output while those 12 days without wind meant a loss of over 3,000 GWh of generation. Without significant long-duration storage, the plans for more wind generation will leave the market very vulnerable to low wind conditions, and will threaten the 2035 electricity de-carbonisation target.

Ambitions for new nuclear fall far short of what is needed

The plan to secure a final investment decision on large-scale nuclear by the end of this Parliament is also hardly ambitious – there are still three years remaining in this Parliament, and by then much of the existing nuclear fleet may have been forced to close. These decisions needed to have been made in the last Parliament, and further delays present real risks to security of supply, particularly in low-wind weather conditions. An additional £120 million of investment on top of the £525 million announced in the 10-point plan is still woefully inadequate – more is needed, and faster.

Depressingly the document refers to Sizewell C in the context of a new large nuclear project. This is really not a good idea, and the Government should not be betting on the troubled EPR technology until EDF has demonstrated its ability to actually deliver such a reactor in Europe – its first EPR project at Olkiluoto in Finland was originally due to open in 2009 at a cost of €3.7 billion. It is now unlikely to open before 2023 (the official latest date is 2022, but this seems unlikely given the schedule) at a cost of at least €12 billion. The flagship EPR project at Flamanville C was supposed to open in 2012 at a cost of €3.3 billion – it’s opening has been delayed to 2024 and its cost has risen to €19 billion.

In contrast, Hinkley Point C was expected to open in 2025 at a cost of £18.1 billion, but it is now delayed until mid 2026 and its cost has increased to £23 billion. The initial estimates for HPC were for a much longer construction period and much higher costs than the original estimates for Olkiluoto and Flamanville, undermining the arguments that subsequent units can be built faster and cheaper (a theory which in any case has been debunked by this MIT study).

Bioenergy provides a false sense of security

The Government intends to publish a bioenergy strategy in 2022, building on what it sees as the success of biofuels in electricity generation to date, with bioenergy accounting for 12.6% of total renewables generation in 2019. Unfortunately, as this excellent paper from Chatham House (thanks to It doesn’t add up… for the link) points out, there are some real challenges with bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (“BECCS”) which are often over-looked.

“However, the reality of supply chain emissions and potential carbon debt could result in wood-pellet-based BECCS failing to deliver the negative emissions that are technically possible…In influential IAMs [integrated assessment models]…biomass is assumed to be carbon neutral, efficiency and capture rates are exogenous inputs to the models, and the models lack transparency. In the real world, biomass supply chains embody non-marginal emissions and there is a clear trade-off between the efficiency and capture rate. While scientists treat models as ‘experimental sandpits’, policymakers tend see them as ‘truth machines’,”

– Dr Daniel Quiggin, Senior Research Fellow, Environment and Society Programme, Chatham House

The emissions from the drying, pelleting, transportation, and piping of the CO₂ to storage sites are not insignificant and are often not correctly included in the de-carbonisation analysis. Assumptions around the carbon-neutrality of the wood-biomass to begin with can also be flawed, since they depend on complex calculations involving growth rates and forestry management methods, while the increase in wood-pellet biomass to supply the amounts of BECCS assumed in many net zero plans also has serious implications for land use and competition with food production.

The Government is wedded to its flawed approach to the retail market

The Government states that “consumers should pay a fair, affordable price for their electricity”. Earlier this year it published a strategy for the retail energy market, a 17-page document which outlined the Government’s intention to continue with the current – flawed – market structure, tinkering with it rather than reforming it.

Of course, part of this strategy is the retail price cap, which the Government seems to believe is essential to stimulate investment in improvements in supplier IT infrastructure among other things, apparently unaware that the cap means consumers are not in fact paying a fair price for their energy, and that forcing suppliers to sell energy at a loss means they will almost certainly reduce investment in IT and everything else.

Of course, part of this strategy is the retail price cap, which the Government seems to believe is essential to stimulate investment in improvements in supplier IT infrastructure among other things, apparently unaware that the cap means consumers are not in fact paying a fair price for their energy, and that forcing suppliers to sell energy at a loss means they will almost certainly reduce investment in IT and everything else.

The Government also seems wedded to a flawed interpretation of consumer behaviour, assuming that lack of switching means lack of engagement, and that the only motivation for switching is price. The characterisation of customers choosing “old-fashioned tariffs” as something to be remedied ignores the other supplier characteristics such as good customer services which may secure customer loyalty.

The recent market events have shown challenger suppliers offering low tariffs are exiting the market in droves, taking those low tariffs with them. It is entirely possible that consumers will be deterred from signing up to cheap tariffs in the future as a result, which has significant implications for the Government’s opt-in/opt-out switching plans: how happy will customers be to be automatically switched to a supplier that then folds, or has terrible customer service?

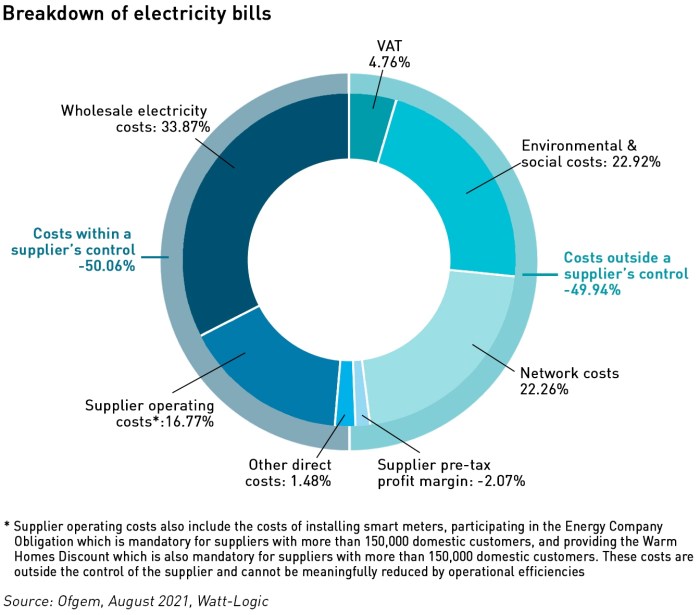

The Government wants to see suppliers developing innovative business models that support net zero, but this is completely unrealistic under the current market structure. Even before the current crisis, energy supply was a low margin business, with suppliers having limited control over their costs due to the large amount of non-supply activities they are forced to undertake. The Government believes competition is the means by which value is delivered to consumers, yet the number of suppliers has fallen by a third since the introduction of the price cap, and the very limited ability for suppliers to control their costs further reduces the scope for competition.

While consumer protection is important, the price cap is the wrong way to deliver it. Instead, the FCA Principles should be applied to the energy market, and even regulation of suppliers passed to the FCA, since energy supply is largely a virtual business, with Ofgem continuing to regulate the physical energy market. Requiring suppliers to treat customers fairly, maintain adequate financial resources, and protect customer credit balances would be a very good place to start, and these protections should apply to all energy consumers and not just the domestic segment.

Heating: the Government talks about low-regret actions but fails to identify the most obvious ones

Plans for heat pumps provide too little support to too few homes

The strategy sets out the Government’s hopes that households will transition away from methane to other forms of heating including heat pumps and hydrogen, however the measures outlines fall significantly short of what will be needed.

A £450 million Boiler Upgrade Scheme is intended to provide £5,000 grants for heat pumps (which currently cost in the region of £10,000), but this fund is only enough to support 90,000 households – approximately 0.3% of the total number of households in the country. In addition, because heat pumps provide low grade heat, homes need to be very well insulated if they are to achieve an equivalent degree of heating to existing gas boilers. Most UK homes are not well insulated, so the costs of retro-fitting homes must also be considered.

The Government is also hoping that the costs of heat pumps will fall as more are installed, and that they will be “as cheap to buy and run as a gas boiler”. It wants to see 600,000 installations per year by 2028 with costs falling by at least 25-50% by 2025, and to parity with gas boilers by 2030 at the latest. (At this installation rate it would take 46 years to fit heat pumps to every UK home, and while it is not expected that every home will have a heat pump, this gives an indication of the scale of the challenge compared with the size of the Government’s ambitions.)

Reducing heat losses from buildings will fail to work unless the system is reformed

Predictably there are also plans to upgrade homes to EPC Band C by 2030 “where reasonably practicable”, with an additional £1.75 billion of funding. The Government plans to consult on minimum performance standards to ensure all homes meet EPC Band C by 2035, “where cost-effective, practical and affordable”, and setting long-term regulatory standards to upgrade privately rented homes to EPC C by 2028, and privately rented commercial buildings in England and Wales to EPC Band B by 2030.

“Prioritising no or low regrets actions. Reducing bills through a fabric-first approach to improving building thermal efficiency through, for example, insulation, draught-proofing and increasing the energy performance and capability of products and appliances,”

– Net Zero Strategy

Unfortunately the report repeatedly makes the error of describing the EPC as an “energy efficiency standard”, which is incorrect, and these plans will fail to achieve the desired objectives of reducing heat consumption unless the calculation methodology is revised. Unfortunately performance-based measurement schemes are only under consideration for commercial and industrial buildings, but many households will suffer if the calculation methodology is not changed in the domestic sector as well.

Only 5 of 125 respondents to a Government consultation on the described EPC reliability as “good”, with 60% of respondents highlighting input errors, and respondents highlighting the fact that EPC “doesn’t take build/install quality or deterioration of materials into account”.

73% of respondents believed the EPC was not effective. There is growing evidence, cited by respondents, that the energy consumption of new dwellings can be up to 200% higher than predicted by the EPC, and that similar buildings can receive very different EPC results.

Households can easily be led into invasive and expensive projects to secure a better EPC rating when improving the condition of the building could well have a higher impact on heat losses (but no impact on the EPC). A genuinely low-regret investment would be to identify the actual cause of heat losses and fix faulty installations before attempting to install new measures.

Plans for hydrogen but little money being made available

In addition to incentivising heat pumps, the Government hopes to see 5 GW of hydrogen production capacity built in the UK by 2030. The Industrial Decarbonisation and Hydrogen Revenue Support scheme has been created to fund hydrogen and industrial carbon capture business models, with up to £140 million being made available including up to £100 million to support electrolytic hydrogen production facilities up to 250 MW in size. There is in addition to the £240 million Net Zero Hydrogen Fund to support low carbon hydrogen production.

It plans to establish large scale trials of hydrogen for heating and to take decisions in 2026 on the role of hydrogen in heating, consulting on the case for enabling or requiring hydrogen-ready boilers and broader heating system efficiencies.

Transport plans remain centred on electrification and hydrogen

The Government plans to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2030, and introduce targets for the percentage of new car and van sales to be zero emission each year from 2024. An additional £620 million is being committed to support the transition to electric vehicles, supporting the rollout of charging infrastructure, with a particular focus on local on-street residential charging, and targeted plug-in vehicle grants.

£12 billion is to be invested in local transport systems over the current Parliament with £2 billion to ensure that half of all journeys in towns and cities will be cycled or walked by 2030. The National Bus Strategy will be supported by £3 billion of funding, to create integrated networks with more frequent services, with 4,000 new zero emission buses using batteries or hydrogen and the infrastructure to support them. More of the railway network is to be electrified, with an ambition to remove all diesel-only trains by 2040. £180 million of funding will support the development of sustainable aviation fuel (“SAF”) plants, to enable the delivery of 10% SAF by 2030.

The Government remains highly committed to the electrification of light vehicles, and a greater use of walking and cycling as an alternative to driving. This is a significant challenge – not only does this strategy mirror that followed in other countries, creating high demand for the scarce minerals used in EV batteries (which are not actually very sustainable), but car reliance has increased over the past year as people have become more reluctant to use public transport, although EVs have recently become more popular given concerns over fuel shortages.

The Net Zero Strategy is disappointingly one-dimensional

What is striking about the Government’s plans is that they are really one-dimensional. In the power sector there is a huge focus on more wind capacity, but little else of substance – elsewhere the story is all about electrification and hydrogen. Much depends on technologies which are as yet immature and un-proven, but there is only an additional £500 million of innovation funding, bringing the total investment in net zero research to £1.5 billion. This compares with around £2 billion of investment in EVs and EV infrastructure alone.

It’s difficult to see how the electricity system will cope with these additional demands and absorb the huge planned increase in wind generation without a similarly large commitment to new nuclear and long-duration storage. Without these supporting investments, the system will be too insecure to rely on renewable energy, and fossil fuels, particularly gas, will continue to be needed to fill the gaps. The huge “subject to security of supply” caveat in the net zero target for the power sector provides an enormous get-out of-jail-free card which will almost certainly be needed.

We can expect to see gas plant continuing to succeed in capacity market, particularly OCGTs and small gas engines – the last T-4 auction saw some really big, 700 MW OCGTs being awarded contracts. This means that the capacity market continues to incentivise less environmentally desirable technologies (since CCGTs have lower emissions and would usually be the preferred approach for larger plant).

Nothing in the Net Zero Strategy addresses the near-to-medium term capacity issues in the electricity system, so we can expect current trends to continue: high and volatile winter prices, and an increasing risk of load shedding in low wind weather conditions, particularly in winter.

This is a really good breakdown of the government’s strategy (or lack of) for Net Zero. You nailed it at the start when you said you could add ‘Once upon a time’ to the PM’s speech – he appears to be living in fantasy land where net zero can be reached without radical changes to our energy consumption and production, some of which will have to involve an element of coercion for business and consumers, as well as incentives. The continued faith in the ‘invisible hand’ of the market to magic up commercial scale innovative technology is also disappointing. We need to have a relentless focus on reducing energy consumption to as low a level as possible in domestic and business properties as the move towards electric heating and electrified transport will increase demand elesewhere in the system. This government is unwilling to be honest with the public anout the level of change that is required in the next 10 – 15 years which makes reaching their targets very unlikely.

No Government has been honest about either costs of de-carbonosation or the lifestyle changes needed since the 1990s when this all started. There’s far too much muddled thinking around reducing consumption and improving energy efficiency – it should be a no brainer, but low regret actions get obscured by all sorts of other nonsense. I thin kit highly unlikely the targets are met, but I also think that’s a good thing as long as we’re not bankrupting ourselves and destroying security of supply in the process…

Fantasy and delusion. I am surprised that you are a lone voice in raising the unreality of this ‘Once upon a time’ approach rather than a properly engineered plan using established technology. At the heart of this is a battle between power and energy. Working in energy terms (not always through ignorance) conceals many unresolved issues. Previous White Papers have been in Power terms for electricity strategy but the latest is in Energy terms (even the chapter titled Power barely mentions the concept). Has the motto changed from ‘Power in Trust’ to ‘Energy with Delusion’?

A simple model that matches supply and demand for both power and energy shows that the strategy proposed, although containing many business opportunities, will be very expensive and not get close to Net Zero. A wrong turning has been taken on the road to zero. Do not despair. The model shows there are solutions out there.

I doubt many people in Westminster or Whitehall understand the difference between power and energy. They just think we can solve everything with more wind. I’ve spoken with people recently that struggled to appreciate the limitations of solar power (eg not being available at night-time….)

Another excellent article Kathryn.

What an excellent critique of government policy and strategy (or lack of!). This is expert detailed opinion which I value highly. A shame we seem to have a government with different priorities! Please keep up the good work Katherine I really look forward to your blogs.

A useful critique – thank you. I don’t accept your implication that there is a solution but the Govt has not found it. I certainly accept that the Govt is in cloud cuckoo land on this subject (as in so many), but I would argue that there is no solution that humankind is willing to implement. This is not a UK issue, but a world one, and one which the world loves to talk about but does almost nothing. The adjustment costs are just too great for politicians (and probably for most people). I will only believe someone is serious when they start talking about populations levels and the need to get them down to a level which is consistent with sustainable ecosystems. It’s not just excess carbon production which is screwing up the planet and killing off other lifeforms.

At the risk of making your readers explode with anger (but also hopefully causing them to think rather differently), a possible saviour of the world might be a virus rather more deadly than Covid19 which could halve the world’s population while humanity acquired immunity. Of course, even with a vastly reduced human population, there would still be the need for humans to develop a respect for all the other life which shares this planet with us. Some “uncivilised” peoples have had this in the past, but it is notoriously lacking in modern western societies where shopping is regarded as a pastime and consumption the main aim of life.

I’m not really a fan of the Malthusian Theory of Population and tend to agree with its critics that technology and economic development provide the means by which human populations can sustain themselves. Interestingly, more developed nations tend also to have lower birth rates – in the UK the birth rate has been below the replacement level for some time, leading to concerns about a shrinking base of taxpayers having to fund the elder care of a large population of retirees.

However I agree that the necessary adjustments to achieve net zero will not be achieved without major technological advancements which almost certainly need to be in the area of cheap and reliable energy generation, and/or flexible, scalable long duration storage solutions. If we can get mini molten salt reactors to work they would have huge potential…

Hi Kathryn……great post exposing the muddled thinking around such an important topic.

In the meantime the clock is ticking.

Surprised & disappointed once again tidal barrages fail to get a mention.

When will our politicians realise that barrages provide so much more than electricity generation ?

The moon rotates around our planet predictably each month creating all the energy we need.

Harnessing this fantastic resource needs funding on a par with wind, solar, & the disappointing nuclear builds.

I feel the “Once Upon a Time” & “Fantasy World” reference in the original posting provides licence to include my thoughts & feelings. I make no apology for the lack of scientific fact & stats. but here goes with my pie in the sky.

Again on a local theme Morecambe Bay is a vast area of 340 sq. km, larger than Sydney Harbour.

The barrage supporting a toll free carriage way would link Barrow & West Cumbria with the main transport motorway network, reducing the journey time between Heysham & Barrow from 2 hrs to 30 mins. This opens up ready access to an important large industrial conurbation, levelling up springs to mind.

Wind turbines along the 17 km highway could also support lighting structures along the carriageway.

Embedded beneath the roadway 132, 2-way tidal turbines.

The intertidal lake could provide for floating islands of solar panels, currently being installed on many UK reservoirs.

Also the potential for leisure plus control of the annual flood threat that blights hundreds of homes & businesses around the bay.

I still fail to appreciate why the additional benefits of tidal barrages around the UK coast is not fully realised. Surely collectively they could provide all the green energy we need, a fantastic carbon free by-product.

Sticking with my local theme maybe now’s the time to retrieve & dust off the excellent forward thinking Northern Tidal Power Gateway (NTPG) project (2014) see attached:

http://www.cumbriachamber.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/NTPG_update.pdf

But as I say pie in the sky.

Barry Wright Lancashire.