Six more energy supplier failures have been annouced this week. Monday saw the closure of Bluegreen Energy (which supplied around 5,900 domestic and a small number of non-domestic customers). On Tuesday four suppliers ceased trading: Zebra Power (around 14,800 domestic customers), Omni Energy (around 6,000 domestic pre-payment customers), Ampoweruk (around 600 domestic and 2000 non-domestic customers) and minnow MA Energy (around 300 non-domestic customers). This evening, CNG has also announced its closure (see below).

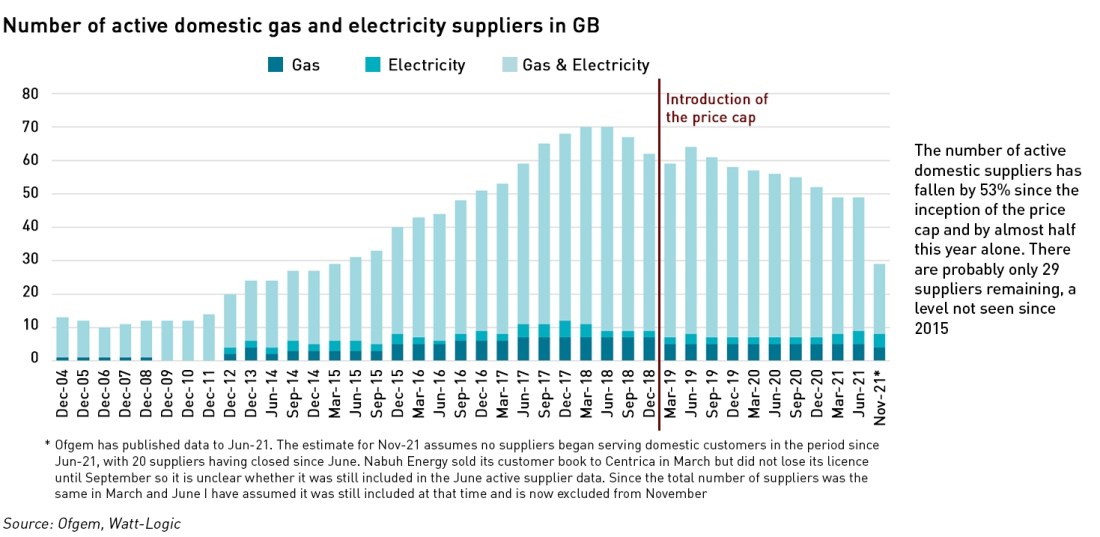

This brings the total of failures now to 23 this year, of which 21 served domestic consumers. This represents almost half of the market – according to Ofgem there were 52 active suppliers in the domestic market in December 2020 falling to 49 in March this year, and the same in June. The Ofgem data are slightly confusing because it also publishes data on the suppliers entering and exiting the market which includes a running total and these data appear to lag the total domestic supplier figures by one quarter. It seems unlikely that any suppliers have entered the market since June given current market conditions, which means there are probably just 29 active suppliers serving the domestic market, a level not seen since 2015.

If we are to believe the Government’s narrative that only poorly run supply businesses are failing, then surely we must ask how is it that Ofgem is presiding over a market where almost half of the market participants are “poorly run”. Surely this is the very definition of a regulatory failure?

Renewables Obligation defaults signal further supplier distress

Last week Ofgem announced various actions in respect of Renewables Obligation (“RO”) defaults in respect of the compliance year 2020/21 which ended on 31 March. The late payment deadline passed on 31 October with a number of suppliers failing to meet their obligations, often a pre-cursor to a market exit.

Earlier in October, Ofgem had identified five suppliers who were likely to default. Of these three have since ceased trading, one has paid in full, while another, Whoop Energy has been issued with a final order in respect of its arears of £56, 306.25 plus interest. A further five suppliers have also been identified as being in default, one of which was in the group that ceased trading yesterday. The other four, Delta Gas and Power, Entice Energy, Neon Reef and Together Energy have been issued with provisional orders. These four plus Whoop Energy are clearly under pressure and may well be the next to close.

Unfortunately for those suppliers that have met their obligations, they will now face a large mutualisation bill in respect of the failed suppliers. I previously estimated the amount to be in the region of £187 million – the largest ever shortfall, double the previous record, which will now be covered by all other suppliers in proportion to their market share. The sheer size of this bill is unlikely to have been factored into their budgets for this year, and it will almost certainly create additional stress, particularly for smaller suppliers.

The fallout from the CNG failure has yet to filter through

Three weeks ago saw the announcement that gas shipper CNG was to exit the market. In addition to supplying 40,000 small and medium-sized businesses directly, CNG provided gas shipper services to 18 other energy suppliers, some of whom also procured their gas through CNG. CNG announced that its insolvency advisors had advised that the gas they had procured on behalf of these suppliers, and any associated hedges, are considered assets of the business and cannot be assigned to the suppliers. This means that those suppliers must not only find a new shipper, but they must also replace those hedges at current, higher, market prices, and provide the collateral to cover this trading activity – it is unclear whether CNG is in a position to return the collateral it holds on behalf of these suppliers.

According to Bloomberg, CNG will cease trading on 30 November at which point suppliers will have up to a further 25 days to find a new shipper, although they would first need to post collateral and buy forward for December before the end of this month. CNG has failed to find a buyer for its supply business and as I was writing this post, it announced it has asked Ofgem to appoint a Supplier of Last Resort.

.

For those suppliers that have managed to make their RO payments and are not affected by the CNG issue, the wider challenges in the market remain. The Credit Assessment Price which determines the level of collateral suppliers must provide to Elexon is set to jump from £184 /MWh to £259 /MWh from tomorrow, and with wholesale gas and electricity prices continuing to be above the level allowed in the price cap, it is almost certain that more suppliers will fail in the coming weeks.

Good piece, thanks. I wonder if in a future piece you could address the issue of what these company failures mean for the green credentials of consumers’ electricity. My suspicion is that the answer is “nothing at all” because green tariffs actually don’t drive renewables development to any significant extent – even those that offer both REGOs and a specific renewables supply contract. This frustrates me because I’m trying to develop local behaviour change programmes that actually make a difference, keep facing the suggestion that as step 1 consumers should buy a green tariff, and fear that in practice this is window dressing.

Green tariffs don’t drive the development of more renewable generation, unfortunately. The price of REGOs is much too low, which is why all of the other subsidies are needed. Green tariffs are window-dressing because consumers generally receive the carbon intensity of the grid (actually they get whatever is nearest because the network is “real” ie has transmission losses and congestion issues). Very few consumers understand this – I have dealt with businesses which think they can be “net zero” in 2025 because they have a green tariff and when I explain this isn’t real they are genuinely shocked.

It seems quite probable that most of the fault for these failures is OFGEM’s. I can’t see any advantage to consumers in having 60 or more energy suppliers. They cannot have any distinctive features that mean customers are gaining an advantage and, most of the failed suppliers are comparatively tiny.

OFGEM allowed the proliferation of suppliers run by chancers and wide boys and the difficulties with high oil and gas prices has sunk them. An intelligent regulator would have ensured energy suppliers had more robust finances and had sound management. I read your last post which identified that scrapping OFGEM may not be effective, but what is the alternative?

My preferred option is to move the regulation of suppliers to the FCA. That gets round the issue of scrapping Ofgem which would just be re-branding, this is moving a part of the remit to an existing other regulator.

Otherwise I agree – most of the reason for these failures is the way in which Ofgem is regulating the market, particularly the price cap.

Another interesting piece.More turmoil on the periphery. Keeps life interesting and no doubt gives jobs and a good living to those involved in sorting it out.. Is it productive? How does it lead to lower CO2 emissions?

Administrators are making a tidy sum out of all these failures and you can be sure the directors have had plenty out of them before throwing in the towel. This is an utter failure by the government who have encouraged consumers to switch to save and find themselves now on more expensive tariffs. Also presumably the rest of us will also have to pick up the 187m pound bill that Kathryn refers to above which looks like it will get worse as a negative feedback loop will drive the majority of the remaining suppliers out of the market.

The Government’s view of the market is overly simplistic and boils down to:

more suppliers = more competition = better deals for consumers

But this assumes “better deals” = “cheaper deals” which is only true of consumers only value price and not anything else. And if low cost suppliers fail those “better deals” disappear forcing consumers to pay more.

It’s not rocket science….

Energy supply is a largely virtual business, so I don’t think it makes a difference either way to emissions.