It’s always interesting at this time of year to look back over the past year and ahead to what might be expected in the year to come. This time last year, I expected the retail price cap to be big news, alongside new nuclear, changes to balancing markets, the growing impact of digital technologies, a more challenging environment for battery storage projects, and a heating up of the gas market.

“Other areas I think may well see some prominence in the coming year include further changes to the operation of and charging for the transmission system; the impact of new digital technologies on the sector, particularly blockchain; and a slowing of the development of new battery storage as revenue models face strain. 2018 could also be an interesting year for the gas markets, with recent news on hydrogen, as well as changes in global market structures.”

As always, some of my predictions were right and others completely wrong! The retail price cap did indeed dominate headlines, and has just come into force with the start of this year – more on that later – and there were major developments in the nuclear space with the expectation of direct Government support for the Wylfa Newydd project, and the cancellation of the Moorside project. Towards the end of the year there was speculation that the Wylfa project may go the same way as rising costs could deter sponsor Hitachi – nuclear is likely to remain in the news in 2019.

2018 also saw the world’s first European Pressurised Water Reactors (“EPR”) – the same technology as Hinkley Point C – go into service in China after years of delays and cost overruns. The flagship Flamanville project continues slowly on its development path with further construction issues.

Batteries did face a more challenging market in 2018, although there were also major developments, with the deployment of battery installations of increasing size around the world: installed battery capacity in the US exceeded 1 GW in 2018. Regulatory change, particularly around network charging, presents some threats, as does the removal of capacity market payments from the income stream, although this may only be temporary (see below).

Another emerging challenge for batteries this year has been around fire safety, with the occurrence of several battery fires over the past year. However, the developing markets for flexibility should provide new opportunities for batteries – December saw the launch of a new 49 MW fast response battery project on the site of an old coal-fired power station, benefitting from existing grid connectivity although there were challenges relating to the scale of the required cooling systems and anti-corrosion measures due to its coastal location.

On the digitisation front, progress continues, but there has been no revolution over the past 12 months. Having spent some time looking into the potential impact of digitisation on the energy sector over the past year (there will be some posts in the near future on this), I’m much less persuaded that blockchain is going to be a game changer in energy, since the energy intensity of the distribution and verification process will be a limiting factor.

Similarly, gas markets have seen a great deal of volatility, and there is increasing interest in the use of hydrogen, but there has been no major shift in market structures over the past year.

There have been some major announcements from Ofgem on transmission charging, and this is likely to continue to be a major theme for 2019.

Energy policy going no-where, slowly

When looking back over 2018 it is also interesting to consider the overall policy actions from the UK Government, described very well in the 2018 review from Cornwall Insight, as being broadly lacking in substance aside from the creation of the price cap. Energy Minister Claire Perry is targeting a net zero carbon position but so far there are no new policy mechanisms that might deliver this goal, and there are concerns in the industry that the fourth and fifth carbon budgets are unlikely to be met.

In power, the third Contract for Difference (“CfD”) allocation round will take place in May 2019, but uncertainty remains about the long-term future of the carbon price floor after 2021, with suggestions that the level may be cut. The five-year review of the Electricity Market Reform was described by Cornwall Insight as an “exercise in re-arranging the deck chairs”, and although Business Secretary Greg Clark has declared the “trilemma” to be over on the basis that subsidy-free renewables would be the cheapest energy available from the mid-2020s, there was no significant new policy direction announced with critical issues being left to the Energy White Paper expected in 2019.

A Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (“CCUS”) action plan published in November failed to deliver anything concrete, and suggests that CCUS will not be deployable at scale until the 2030s. This is probably a good thing since there is no evidence that CCUS is economically viable except alongside hydrocarbon production, so the Government would do better to focus on other areas (it would do better still to draw a line under CCUS altogether).

The flagship “Road to Zero” transport strategy lacked ambition and disappointed many in commitment to phasing out conventional vehicles and its vagueness in defining Ultra Low Emission Vehicles. Similarly, there is no credible framework for delivering emissions reductions in heat.

Cornwall Insight expresses the optimistic view that no policy vacuum can persist for long and that 2019 may therefore emerge as the year in which progress re-emerges:

“2019 could be the year in which Government re-asserts a strategic grip over the energy policy agenda, simply because it has no other choice. It will be compelled to focus away from the retail market. A policy paper is said to be imminent, preparing the way for the White Paper.”

However, it is likely that the Government will continue to be pre-occupied with Brexit, and the potential negative outcomes of the retail price cap may keep attention firmly focused on the end-user segment after all.

Looking ahead to 2019 I expect the top 5 areas of interest in energy to be:

#1: The retail price cap

The retail energy price cap finally came into force on 1 January at a level of £1,137, although Ofgem has already indicted that rising wholesale prices may lead to an increase in the level from April, to be announced in February. The cap level of £1,137 is just £84 cheaper than the average standard variable tariffs of £1,221 available in November (the most recent figures from Ofgem), and £191 more expensive than the cheapest available tariff at the time.

According to Ofgem, 11 million households on poor value default tariffs are set to save around £76 on average, while a typical consumer on the most expensive tariffs would save more than £120. Any benefits could quickly be eroded by rises in the cap level as wholesale prices continue to rise (although arguably, tariffs might have risen more without the cap):

“There is a very good chance that the price of standard tariffs will change three times over the next 12 months, and potentially for the worse rather than the better,”

– Richard Neudegg, head of regulation at uSwitch.com

Consumer groups have welcomed the introduction of the cap, however elsewhere there are concerns, with Lawrence Slade, chief executive of Energy UK saying that the price cap will present a significant challenge for many suppliers since many of the costs they face are out of their direct control.

Others worry that the existence of the cap will deter consumers from switching suppliers to secure better deals, and that cheaper deals may be withdrawn from the market altogether – according to research by Which? there were only 8 dual fuel tariffs cheaper than £1,000 in December, compared with 77 in January 2018. The cap will also not protect consumers on expensive fixed price tariffs as it only applies to default tariffs.

In December, British Gas owner Centrica announced that it is seeking a judicial review of the way in which Ofgem calculated the wholesale costs used in setting the cap, specifically the “treatment of wholesale cost transitional arrangements and Ofgem’s decision not to investigate and correct its failure to enable the recovery of the wholesale energy costs that all suppliers incur”. Fellow Big 6 supplier npower welcomed the legal challenge, telling Utility Week:

“Throughout the SVT [standard variable tariff] price cap consultation process, we’ve been clear that we have serious concerns about calculations that led to the level of the cap. We believe the cap will be damaging to the energy industry, to investment in the UK and, ultimately, to customers – which is why we think Centrica are right to bring a legal challenge,”

– npower

Ofgem said it will defend its proposals “robustly”.

Whether or not this legal challenge is successful, the retail price cap will have a major impact on energy markets this year. An increase in the cap level as early as April will be politically uncomfortable, despite being potentially necessary to reflect changes in wholesale markets, and the effects of the cap on the competitive landscape will continue to unfold over coming months (see below).

#2: The retail supplier landscape

The competitive landscape for retail energy suppliers is increasingly difficult. 2018 saw the closure of several* small suppliers and the cancellation of the SSE-npower merger as a result of the impact of the price cap. SSE is now considering other strategic options for its retail business

The cap is expected to add further stress to small suppliers with their reduced ability to hedge wholesale price risks…indeed, the comments made by Energy UK above are correct – the portion of costs faced by suppliers that they are able to control is small, so there are limits to what can be achieved through efficiency savings.

Although the smallest suppliers are not required to pay a portion of policy costs, this benefit does not appear to be enough to ensure competitiveness, as seen by the growing number of company failures in the past year. There is no reason to expect conditions for small suppliers to improve in 2019, so more exits can be expected.

As a result of the difficulties faced by small suppliers, and poor levels of customer service provided by some of these companies, Ofgem is tightening the rules for new entrants to make it more difficult for under-resourced companies to open energy supply businesses. This may mean that alongside the closures of small suppliers, fewer new entrants will arrive to take their place. The overall number of energy suppliers may begin to fall as a result, further reducing competition in the market.

Life is also difficult for larger suppliers – the only UK-listed large suppliers, Centrica and SSE, both issued profits warnings citing the price cap. The larger energy suppliers are re-structuring their business in response to increasingly challenging market conditions – this trend is also set to continue in 2019 as long as supply margins remain under threat. SSE also saw its credit rating cut from A3 to Baa1 by Moody’s in December.

The price cap will impact the competitive landscape in other ways, particularly around tariff availability and switching. With the introduction of price caps into a market, there is a risk that suppliers start to price to the cap, leading to tariff convergence around the cap level. To a certain extent, this was already seen with the prepayment meter cap that pre-dates the wider price cap that began on 1 January.

It will be interesting to see how policymakers respond if the market begins to shrink and the range of available tariffs falls, both of which would reduce consumer choice and potentially lead to market failure that are more damaging than the ones the cap was introduced to address.

* By my count, 14 small suppliers closed in 2018: Brighter World, Future Energy, Flow Energy, National Gas & Power, Gen4U, Electraphase, Spark Energy, Iresa, Snowdrop, Usio, Extra Energy, Planet9 Energy, Affect Energy, One Select. Economy Energy could be next with the news that Ofgem has restricted it from taking on new customers

#3: Network charging

A major market theme towards the end of 2018 involved Ofgem’s proposals for reforms to network charging. In order to ensure that users of the transmission and distribution networks are charged fairly for the costs they impose on the system, Ofgem is pursuing a number of avenues of reform to remove distortions that have arisen as an unintended consequence of recent market change.

There are two main initiatives underway, the Targeted Charging Review of residual network charges and embedded benefits, and the market access and forward-looking charges review taking place as part of the Electricity Networks Access project. At the same time, National Grid and Elexon are both consulting on specific code changes that support Ofgem’s objectives.

Taken together, Ofgem’s reforms cover:

- Forward-looking charging encompassing a comprehensive review of Distribution Use of System (“DUoS”) charges; a review of the distribution connection charging boundary; and a focused review of Transmission Network Use of System (“TNUoS”) charges.

- Residual charging which Ofgem is minded to reform with a fixed charge payable for each demand meter, based on customer segment.

- Embedded benefits reform to set the Transmission Generation Residual to zero, removal of Balancing System Uses of System (“BSUoS”) payments to small embedded generators, and a requirement for small generators to pay BSUoS charges.

- Market access reform clarifying access rights for small users and households and improved definition and choice of access for larger users exploring the potential for varying levels of firmness, time-profiling and tenor for network access rights.

Ofgem is currently consulting on its “minded to” decision on residual charging and embedded benefits, and expects to publish its “minded to” position on forward-looking charging and market access in spring 2020.

The economics of large transmission-connected users practicing triad avoidance will be impacted by the proposed reforms, as will small embedded generators, particularly SMEs connected at low-voltage levels who will see residual network charges increasing and a removal of payments relating to demand-reduction services provided to suppliers.

The changes would make network charging more aligned to the costs and benefits each new generation or demand connection brings to the network. 2019 will see companies across the industry as a whole evaluating Ofgem’s proposals and their potential impact on their business models.

#4: RIIO-2

In December, Ofgem announced its proposals for the next price control round for gas and electricity networks, known as RIIO-2. In the new price control period, which starts in 2021, the regulator has proposed that the allowed cost of equity returns for network operators be set at a baseline of 4% after inflation, significantly lower than the 7% allowed for transmission networks under RIIO-1, reflecting what Ofgem sees as a low-risk environment for network companies.

Ofgem has also said that it wants to adjust the cost of debt annually so that consumers can benefit from falls in interest rates, and is also proposing to replace the retail price inflation measure in its determination of cost of equity, with the newer and generally lower consumer price inflation housing rate as the basis for indexing fluctuations in prices.

The regulator estimates that the combined reductions in the cost of capital (equity plus debt) of network companies will save consumers £6.5 billion over the course of the next price control period, with each 10 bps on the cost of equity equating to approximately £172 million in consumer bills.

The previous price control was criticised as being too generous, so the proposals have been greeted positively by consumer groups, while network companies see the size of the cuts as a threat to innovation and investment.

”This will be entertaining. 4% Cost of Equity with the Fed raising US interest rates to 2.5% yesterday. If anyone thinks they can operate an energy network at a time of significant social change over a period of 5 years and make a reasonable profit with a COE of 4% please stand up. We might just be heading for a Competition referral on this one. Plenty of work to do on both sides of this argument,”

– Richard Hewitt, gas industry consultant

There is a danger that the regulator is over-correcting for the generosity of the previous price control, for example, the risk-free rate was lower in RIIO-1 than expected at the start of the period, but now as rates are starting to show signs of rising, Ofgem should take care not to under-allow for the costs of borrowing over the next price control period. Although an annual re-adjustment could mitigate this risk, that only helps to the extent the network companies finance themselves with short-term debt.

Ofgem had also previously suggested investors may be willing to accept lower returns on network assets due to their lower risk profiles. This assumption should also be challenged against current market conditions as incessant regulatory change over the past couple of years has eroded investor confidence in the energy sector more broadly, a sentiment that could well spill over into the regulated segment.

Ofgem’s consultation runs until mid-March, and the network companies can be expected to make strong representations against such a significant cut in their returns. A final decision on the methodology is due to be published at the end of May.

#5: Europe

2019 is the year of Brexit, and as I write this, the nature of our exit from the EU is still unclear, so it is difficult to predict how the energy markets might be affected. What is clear, however, is that Europe will have a greater impact on the energy market in 2019 than might have been expected even with Brexit, following the ruling late last year by the General Court of the European Union on the legality of the GB capacity market.

The Court’s judgment led to a suspension of the state aid approval for, and therefore the legality of granting aid through, the capacity market. The Government announced the scheme would enter a “standstill period” which prevents it from holding any capacity auctions, making any capacity payments under existing agreements, or undertaking any other action which could be seen as granting state aid, until the scheme can be approved again.

In December, BEIS launched a consultation on proposals for:

- Conducting a replacement T-1 auction in summer 2019 for the T-1 auction which was due to take place in January 2019;

- Changes regarding obligations under and enforcement of existing capacity agreements during the standstill period, with a view to ensuring capacity providers continue to meet their obligations although penalty payments would only be collected after the end of the standstill period;

- Payments for capacity providers that have met their obligations during the standstill period, replacing the capacity payments not received during the standstill period; and

- Arrangements for the collection of charges from suppliers during the standstill period for the purpose of funding deferred payments to capacity providers, and to avoid imposing sudden large charges on suppliers if state aid approval is re-instated to recover amounts not collected during the standstill period.

The consultation closes on 10 January and aims to minimise the market impact of the Court’s judgement until the necessary steps have been taken to renew state aid approval for the overall scheme. Although it is also the case that a “no deal” Brexit scenario would enable to Government to completely disregard the Court’s ruling and immediately reinstate the capacity market in its previous form.

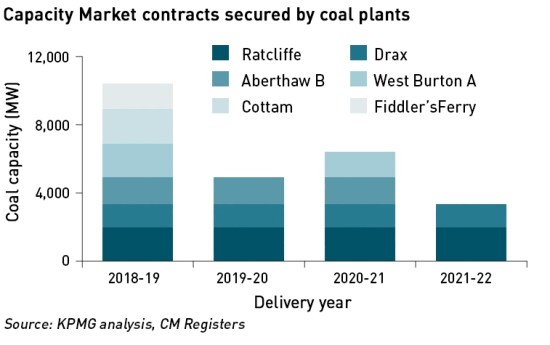

If there is no early resolution to the capacity market suspension, or a Brexit deal is secured that rules out unilateral action by the UK Government, some capacity may start to exit the system due to the lack of capacity payments. Clearly the Government’s proposals are intended to prevent that outcome, but some high cost operators, particularly coal plants, may judge that the risks of remaining open in the hope of recovering some capacity payments may be outweighed by ongoing operating costs.

A “no deal” scenario would also liberate the UK from the other restrictions on providing state aid to the energy sector, enabling the Government to provide direct subsidies to preferred technologies or providers. This could in itself render the capacity market un-necessary, although any replacement would need time to be designed and implemented.

Otherwise, it is still difficult to determine how Brexit will impact the energy markets. It is to be hoped that the next few months will bring greater clarity in this regard.

Whether my predictions for the top 5 energy trends in 2019 turn out to be true or not, it’s safe to say that an interesting year lies ahead, with a challenging environment for just about everyone, and no doubt some surprises to contend with.

Happy new year,

Thanks for wading through all the data & condensing it into something readable; sorry I don’t contribute or comment often, but appreciate what you do.

Thanks – it’s good to know the blog’s appreciated, and all comments are welcome as and when (apart from the weird ones blocked by my security software!)

Always worth keeping an eye here

https://www.bmreports.com/bmrs/?q=balancing/creditdefaultnotice

for those liable to fold. Four companies listed when I looked – Cornflower, Ephase, Faraday and PAL.

Unfortunately until generators bear a much greater share of transmission costs on a locational basis we will continue to have the wrong incentives on grid design – which is to stick generation more or less wherever you choose, and demand that the grid connect you up (or pay you curtailment charges). All baked in in support of renewables for now of course.

I’d be thankful that they haven’t got beyond working out that home charging for EVs will require a “smart socket” that can control the process. In fact, they seem to have made a complete mess of the automotive sector with unclear policy and concern about too much consumer debt.