Energy prices have been in the news again, with price increases from many suppliers and the publication of the intended level of the retail price cap. There are a number of drivers of energy prices, with network and policy costs making an increasing impact on final bills, however the single largest contributor continues to be the wholesale cost of gas and electricity.

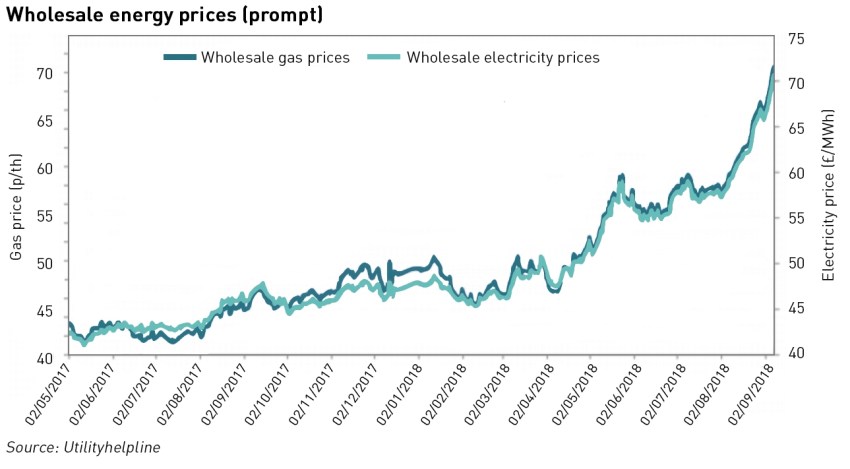

Wholesale gas and electricity prices have been rising rapidly over the past year

After an extended period of relatively benign market conditions, this summer has seen significant price rises for both gas and electricity. Most suppliers outside the Big 6 purchase the gas and electricity they sell to end customers is the wholesale markets through a variety of mechanisms. The markets can be traded “spot” – typically the purchase of gas and electricity for delivery on the following day, or “forward” with products over different time periods in the future. Gas is more liquid in the wholesale markets than electricity, and can be traded further into the future. Within-day trading is also possible.

Ideally, suppliers would buy the majority of their gas and electricity in the forward markets, locking in prices for 1-2 years in the future. This protects them against adverse market movements. A portion of the supply needs would be procured on a short-term basis to reflect the volume uncertainties faced by suppliers, with the intention of minimising exposure to volatile imbalance prices.

Early 2016 saw the lowest wholesale electricity prices for several years, but since then prices have risen by 82%, driven by increases in gas prices (themselves driven by international gas markets and the rising oil price). Winter 18 gas and power contracts are up by 52% and 50% respectively over the last year. Prompt prices have also seen significant increases, with electricity rising almost 50% since the beginning of the year:

Gas-fired power stations are the marginal generators in the GB electricity system, so gas prices play a major role in setting electricity prices. The decline in domestic production alongside the closure of Rough – the UK’s only large long-term gas storage facility – have increased the country’s reliance on pipeline imports from Europe and LNG imports from the Middle East, and now the US. In this sense, Brexit is also making itself felt since as the pound weakens against the euro, the costs of these imports has risen.

Weather is also playing a role, with the impacts of the “Beast from the East” in the spring, followed by an unusually long and hot summer. The increase in solar generation has been met by an increase in load through air conditioning (particularly in Asia which has driven global prices up), meaning that European gas stocks have not had the opportunity to recover ahead of the coming winter.

The high temperature/high pressure weather systems this summer have affected European power generation with nuclear stations reducing output due to problems with cooling, and low wind depressing renewables output.

Finally, there has been a significant increase in the price of EU carbon allowances this summer, from just under €6 /tonne a year ago to a high of €21.8 /tonne on 27 August. The requirement for generators to procure allowances for the carbon they emit means that these costs influence both the merit order and the wholesale price of electricity (see box below).

While short-term (intra-year) weather patterns have a fairly short-lived impact, the other drivers of electricity prices are more fundamental, and unlikely to reverse any time soon – gas and power contracts for Winter 19 have also risen over the past year, but by a smaller degree – 34% for gas and 38% for electricity.

Wholesale price rises putting real pressure on suppliers

When wholesale prices rise, prices to consumers will rise irrespective of the buying strategies of the suppliers. Larger suppliers with comprehensive forward hedging programmes will be able to absorb some price increases since a significant portion of their supply will benefit from fixed prices, limiting their spot exposure. However, future supplies also need to be secured, so while companies may adapt their forward purchasing programmes in response to market conditions, they will generally want to avoid speculating on falling prices since prices could rise further, meaning they may end up locking in higher prices for future supplies if forward prices rise in line with prompt prices.

For smaller suppliers the picture is significantly more complicated due to their limited access to forward markets. Despite Ofgem’s efforts with the Supplier Market Access regulation, market access remains difficult for small suppliers due to their problems with securing trading credit lines. Buying forward creates a credit exposure for the seller with respect to the buyer, since the buyer is bound to purchase an agreed volume at an agreed price at an agreed time.

If the seller is a generator, a default by the buyer will mean it would have to sell its production in the spot markets which may mean achieving a lower price (and exposing the generator to a potential negative spread if it had purchased its fuel forward at higher prices). If, on the other hand, the seller is not a generator, it will have hedged itself in the forward markets and will be itself committed to purchasing on similar terms.

As a result, sellers face significant credit risks with respect to the buyers and will therefore seek to mitigate those risks, by either taking collateral, requiring margin payments to be made, or restricting the volumes and tenors it will trade with any individual buyer.

This is problematic for small suppliers who typically lack the resources to provide either collateral or margin payments, and therefore find themselves locked out of the forward markets, leaving them fully exposed to spot prices.

Smaller suppliers therefore must immediately pass market price increases on to their customers to avoid incurring losses. This is also problematic since many smaller suppliers seek to compete on price, in particular by offering fixed price contracts which leave them exposed to rising market prices.

In a rising market, larger suppliers with forward hedging programmes will have more flexibility around the timing and size of any price increases and will have been able to fully hedge their fixed price tariffs, while smaller suppliers will face significant pressure to pass on all wholesale increases in full as soon as possible, potentially damaging their competitiveness, and potentially absorbing losses on fixed price contracts.

Smaller suppliers that lack the ability to buy forward are suffering not just from the inability to secure their procurement costs into the future, they are also missing out on the ability to take advantage of the current backwardation in gas and power prices. Forward markets are in backwardation when the prices for forward contracts decrease the further in the future they are delivered.

This tends to reflect current short-term supply/demand issues rather than any fundamental expectation of lower future prices, however smaller suppliers that cannot buy forward are fully exposed to those short-term pressures.

These dynamics are putting significant stress on the finances of smaller suppliers – five have already closed so far this year, and more are likely to follow if current market conditions persist. And suppliers across the board are raising their prices – in the case of challenger firm Bulb Energy, for the third time this year, this time by just over 11%.

Impact of the price cap

Ofgem expects its methodology for assessing the wholesale costs contributing to the retail price cap to influence the hedging behaviour of suppliers. It sees wholesale costs as the most challenging aspect of setting the price cap, and has indicated it will use a “6-2-12 semi-annual approach” to calculate the weighted average wholesale cost of gas and electricity over a 12-month period, which involves a six-month observation period of daily index values in the lead up to the cap period, a two-month lag before the cap level is announced and a 12-month forward view of contracts delivering during 12 months following the start of the price cap.

Ofgem has considered various different approaches for benchmarking for wholesale costs, each of which has its challenges. Reported wholesale costs vary significantly between suppliers depending on their purchasing strategy, particularly how far out they have hedged, and the impact of shaping, imbalances and transaction costs must also be taken into account.

Stakeholders raised concerns to Ofgem that the 6-2-12 semi-annual model would prevent them from being able to fully hedge against price changes, because the level of the default tariff cap in any single six-month price cap period is based on prices for a 12-month delivery period, so to follow it, suppliers would have to buy products outside of the cap period, the price of which would not be used to assess the allowance for the following cap period. Alternatively, they may choose not to closely follow the hedge.

“Suppliers have strong incentives to follow a buying strategy that matches the valuation given by the way we assess wholesale costs. This is to reduce the risk that they incur costs that exceed the allowance included in the level of the default tariff cap,”

– Ofgem

Ofgem believes this is the lesser of two evils since otherwise suppliers may reduce their hedging activities further down the curve (although this could in fact level the playing field in that smaller suppliers already do not hedge very far forward). Ofgem was also concerned a shorter window lead to seasonal variations in wholesale prices feeding through into high winter prices and low summer prices for consumers, something suppliers currently avoid in their tariff structures.

Ofgem has considered how non-energy costs including broker and exchange fees, the cost of operating a trading desk, and the cost of credit and collateral should be treated. The level and materiality of these costs is likely to differ significantly across the supplier group with smaller suppliers paying high market access and collateral costs while larger suppliers are likely to have more substantial and therefore expensive trading operations. In setting allowances for these costs, Ofgem must find a mechanism that allows for different operating models across the sector.

“The nightmare scenario for Independent suppliers without access to infinite cash flow is that costs increase significantly above the cap due to unexpected world events affecting wholesale prices such that their capped SVT tariff becomes loss making and its fixed price customers opt for it at the end of their current fixed term as it will be the suppliers’ cheapest tariff,”

– Bristol Energy

In responding to the various consultations of the issue, suppliers have raised their own concerns, including that the approach could force smaller suppliers to adopt long-term hedging which requires large amounts of working capital.

“We think the method outlined for updating the wholesale price could have unintended consequences in the wholesale market. It will likely cause short term prices to rise as all suppliers’ purchasing aligns with the biannual cycle of price cap increases. The impact will be felt more by non-vertically integrated suppliers, who have less [sic] balancing tools available to them and may have less capital available to hedge over longer periods,”

– Co-op Energy

This is an increasingly difficult market for smaller suppliers to navigate. Unlike the Big-6 and new entrants such as First Utility that is backed by oil-major Shell, most challenger suppliers are neither vertically integrated having access to their own supply, nor have the financial and operational resources to adopt the most efficient hedging strategies. This leaves them very exposed to an increasingly volatile wholesale price environment, and with the cap looming, threatens the stability and sustainability of their business models.

It remains a mystery as to why OFGEM think that price insurance should be a compulsory purchase for energy utility customers. We do not do this with motor fuels, where pump prices respond to spot oil and foreign exchange markets fairly promptly, with longer term cost trends arising from e.g. tougher specifications imposed by politicians for pseudo green reasons factoring in as refiners are forced to add processing capacity (e.g. for desulphurisation).

If we had a readily understood marker pricing basis that produced a monthly price, that would concentrate trading liquidity in the short term, ensuring better price discovery, and reducing the need for long term hedging. It would of course still leave events like the Beast from the East that produced exceptional levels of demand (particularly for gas) at high prices, but it really would not be difficult to weight prices by daily demand to produce the monthly average. For the time being, both power and gas prices are tied to NBP/TTF gas prices, since CCGT is almost always the marginal source of generation. Therefore the expectation is that much electricity hedging is in fact conducted in the markets for gas derivatives.

It is a consequence of government, EU, OFGEM and National Grid policy that we are seeing increasing wholesale price volatility. It would do no harm to have consumers see that, and complain and demand that the policy be changed. However, it would also make sense that price insurance and seasonal loans (the two principal products offered by the Big 6 – soon to be 5?) be offered by specialised institutions, with the costs made explicit. There is no cost given by OFGEM in their indicators for these services, which are therefore simply hidden costs. Banks are far more specialised at offering them (and indeed, they are the main counterparties to the Big 6 hedging desks).

It would not be difficult to require that such products be supplied by entities (possibly subsidiaries of the Big 6 if they wanted to pursue it) with proper banking and insurance licences and credentials, and the requirement to explain to customers why caps, collars, and loans that given them a more even monthly cashflow add to their bills, and what they do and do not protect against (prices may go down as well as up is never even mentioned for price fixes in my experience). At best, customers may get some idea of the cost if they ask about early termination fees. Smaller companies may choose to refer customers to particular banks (logically their main bank, who would have a better sight of the risk they are running)

Small suppliers of course benefit from the exemption from having to re-charge some of the green levies to their customers, which gives them a cost advantage, with the cost having to be recouped from the larger suppliers’ customers. The logic of this is twisted, and designed to compensate them for their inability to compete otherwise under the present regime. The solution is to abandon the exemption, and have a far more sensible regime.

The problem with compulsory hedging is that the smaller suppliers can’t access it efficiently either in terms of tenor or shape, so before making it mandatory, Ofgem would need to solve that. I think some sort of credit support scheme would be needed, funded by industry levy, but it would be important to have controls to avoid giving free credit to financially flaky entities.

In practice, gas is less useful as a hedge than you would think, since the correlation isn’t high enough for hedging. Also, a lot of the banks have significantly scaled back if not exited altogether their physical gas/power trading so the munber of counterparties for these structures is reducing. The energy traders are there, and some oil majors have expanded into power trading, but the banks are less present than in the past.

The final challenge is that even inside the Big 6 the approach to hedging isn’t very sophisticated compared with other industries, mainly because vertical integration has reduced their need to hedge. This is another area where the new entrants face a significant competitive disadvantage.

I completely agree more price transparency is needed, and drawing parallels with fixed/floating mortgage products would help consumer understand the impacts of market price changes and hedging. However, wholesale prices only account for around half of bills, with a large part of the rest being policy-driven (direct recover of policy costs or indirectly through the impact on network charging). Successive governments seem to want to obscure these costs (as energy bills are increasingly a tax-collecting activity by energy suppliers on behalf of the Government) so I doubt there will be any moves for greater transparency any time soon.

The Government claims to want a more competitive energy market, but the result of its policies is making life increasingly difficult for all suppliers. Despite their legacy challenges, the Big 6 have significant advantages from their greater size, greater (in some cases) vertical integration, and the resulting greater ability to manage the effects of wholesale prices on their businesses. And even they are re-organising themselves to defend against the impact of policy changes. I expect to see more new entrants fail over the coming months, despite their green levy exemptions (which I agree further distort the market).

The trouble is that OFGEM’s implicit markers in their standard estimated energy bill assume hedging forward 12-18 months – and that problem persists with the energy cap. I’m arguing that they should abandon that basis entirely for what is in essence a monthly spot average (just as oil prices are strongly linked to daily Dated Brent figures). Of course, when prices fall currently, the “unhedged” small firms prosper, as they can easily undercut the hedged Big 6. However, they get squeezed every time when prices rise. If they have no need to hedge (because consumer hedges are provided by different institutions) then smaller firms can compete by offering a better service. But of course until firms are allowed to buy their energy in a free market, with no compulsion to acquire ROCs or otherwise contribute to green coffers, we will not have a properly competitive market anyway. From that point of view, there is a lot to be said for Stephen Littlewood’s pool price mechanism, where price determined despatch order of merit with no privileged positions. True, it had some drawbacks via the ability of those with portfolios of generating assets to game the system. But NETA wasn’t neater, and BETTA is worse.

Hedging capacity has to come from somewhere – principally suppliers or investors seeking to lock in prices, as speculative short interest in energy markets is typically very limited and confined to professionals who spot overbought markets – and the question is how best to intermediate that to consumers. Leaving it as a black box inside Big 6 companies is non-transparent, and open to various forms of manipulation. Frankly, it’s amazing that OFGEM (and DECC/BEIS) have continued to support this. Then again, it all seems to be part of the attitude struck by the Ed Miliband Energy Act of 2010 that gave green interests primacy over consumers.

Thanks for sharing with us this article 🙂