Last week Energyst published its latest report into the demand side response market, which confirmed the findings of previous reports, that businesses are generally positive about DSR as long as operations are not affected. Un-tapped appetite among SMEs was also identified.

The survey found that triad avoidance is the most common DSR action 57%), with 43% of respondents saying they avoid peak distribution costs (DUoS red bands). 44% participate in the capacity market, 34% in STOR and 30% in frequency response. While few respondents participate in Enhanced Frequency Response, awareness of the programme, was higher than any other scheme. (Total responses, 39.)

According to last year’s study by Charles River Associates for Ofgem, DSR is growing but still has low penetration overall. DSR participation in the capacity market is now just under 3% of awarded contracts, compared with 6% in the more mature PJM market in the US. DSR also makes up 4% of National Grid’s total expenditure on Response and Reserve Balancing services.

There are currently around 2.1 GW of DSR participating in the Balancing Services market, and around 1.4 GW of DSR participating in the Capacity Market (these numbers are not additive). Charles River sees technical potential for up to 14.7 GW of DSR across turn-up and turn-down DSR, and behind-the-meter stand-by generation and batteries, which could generate £110 – £400 million of economic benefits in 2020, rising to £160 – £440 million in 2030 if barriers to BM participation are removed.

There are currently around 2.1 GW of DSR participating in the Balancing Services market, and around 1.4 GW of DSR participating in the Capacity Market (these numbers are not additive). Charles River sees technical potential for up to 14.7 GW of DSR across turn-up and turn-down DSR, and behind-the-meter stand-by generation and batteries, which could generate £110 – £400 million of economic benefits in 2020, rising to £160 – £440 million in 2030 if barriers to BM participation are removed.

“These barriers often relate to regulatory failures that deny the demand side an opportunity to participate in the electricity market or to compete with traditional generation resources in providing services to the grid,”

– Phil Baker, Regulatory Assistance Partnership

The extent to which overall economic benefits would be passed on to consumers remains to be seen, but analysis by SmartestEnergy suggests that around 10,000 UK firms could be making around £20,000 a year in cost savings or revenue by load shifting, with the growth in non-commodity costs providing further opportunities.

Unfortunately, regulatory change, while providing opportunities for DSR, can also lead to income uncertainty. At the Energyst DSR conference last week, delegates noted that the changes to the triad regime were negative for the sector and companies whose DSR business plans relied on triads were unlikely to be able to recover the lost revenues through other means.

Cost of implementation

Another message from the conference, which came across more strongly than in the report relates to the cost of implementing DSR. Speakers and delegates alike reported investigating various DSR initiatives only to find that they would need to upgrade equipment. Organisations wanting to monetise their back-up generators for DSR participation are finding that these generators may not have been actively maintained in decades and as they were not designed for flexible operations, there are costs associated with making them fit for purpose.

New switch gear is also required to allow back-up generators to run in parallel with mains power, to provide enhanced response in the event of mains failure, and to be able to continue running once mains power returns. Installing the facility for remote activation is also generally required as on-site generation was generally activated by on-site operators.

Other issues around ensuring adequate ventilation of generator rooms, and complying with noise and pollution regulations can also add cost, and a number of organisations reported resistance form engineers and unions to the changes to maintenance schedules and daily operations that using back-up generation for DSR would entail.

“The main barrier is cost. You are often told there is no cost [of entry]. But there is a cost associated with updating equipment, particularly switchgear, and also significant costs associated with G59 grid connections,”

– Kathryn Dapré, Head of Engineering, Energy & Sustainability, NHS National Services Scotland.

According to Dapré, the upgrade costs at some older sites could run into six figures, presenting funding challenges. These challenges are exacerbated by the upcoming adoption of IFRS 16 which will require operating leases to be accounted for on-balance sheet

Other speakers identified the costs of grid connections and metering as further barriers to entry, with connection applications being extremely complex and almost impossible for non-engineers to complete successfully, meaning that the sue of consultants adds further costs.

“When I was talking to the aggregator my eyes lit up. But then the quote for the metering came in. For 12 sites, it was well into six figures. That was sobering. If you had that in your pocket, would you spend it [on metering]? It’s a good opportunity but it wouldn’t be the first place I would spend it,”

- Gareth Chaplin, energy efficiency manager at Unite Group.

Realising the value of DSR

Many of the Energyst survey participants felt that the revenue from DSR is both too small and too uncertain to justify the effort. While the overall revenue potential from DSR has been fairly stable, the individual components have been volatile: static FFR has fallen in price, DUoS bands have been flattened and triad payments are being cut significantly. STOR prices have stabilised, but the capacity market prices have been disappointing.

“The problem is when you have a DSR proposal on the ground. For example, if you get a good static frequency response contract at £45k/MW and the site has 300kW flexibility, that is less than £15,000 per site, per year. That is a small amount of money if you are pitching to a global bank, a large industrial client or a telecoms company. It is not worth them getting out of bed for, taking on the business risk that comes with DSR,”

– Lee Stokes, head of demand management at Mitie.

While prices for static frequency response have fallen, the need for faster frequency is likely to increase as the levels of inertia on the system fall. However, the higher prices for enhanced frequency response services are likely to eroded as new assets such as batteries enter the market targeting those revenue streams. Overall, the market for these services is relatively small – possibly as little as 2 GW – so it could easily become saturated.

Route to market

In order to participate in the DSR market, companies need to engage with either an aggregator or a supplier. There are pros and cons of each: aggregators are independent and the DSR provision does not cannibalise their core business in the way it does for suppliers, however unlike aggregators, some suppliers are able to participate in the wholesale market and Balancing Mechanism thereby accessing additional revenue streams. (Ofgen is currently developing plans to widen access to the BM to allow aggregators to participate without a full supply licence.)

A major challenge faced by companies is a lack of standardisation meaning that each route-to-market (“RTM”) provider needs to install its own control equipment at the consumer’s site, in order to activate the DSR service. The applications used by each RTM provider is different, meaning DSR providers are effectively locked in to dealing with a particular supplier or aggregator.

The market is currently un-regulated, and while the Energyst survey suggests companies are comfortable with allowing the RTM providers operational access to their equipment, they are much more cautious around whether the promised economic returns will be realised.

“The power has sort of shifted to the aggregators. They can really charge what they like – and the amount that we get paid is a lot less than it used to be. That is an area of concern because the amount that National Grid is paying some aggregators is still the same – or even higher,”

– Andrew Heygate-Brown, senior energy innovation analyst at Welsh Water.

In response to these concerns, the Association for Decentralised Energy is developing a DSR Code of Conduct, setting out clear rules around how DSR aggregators and suppliers engage with potential customers. The code will cover sales and marketing, technical due diligence, customer service, complaints, contractual arrangements and security, in the hope that RTM providers will see signing up to the code as a source of competitive advantage.

Role of DNOs

While aggregators and suppliers provide the commercial route to market, the physical route to market is via the DNOs. Historically, DNOs have been passive participants in the markets, focusing on delivering and maintaining capacity at a local level. As the electricity system decentralises, there is a need for DNOs to participate more actively, using new approaches to avoiding system reinforcement and taking more account of the impact of the local networks on the transmission system.

Prospective DSR providers report finding the process of securing the appropriate export connections to the distribution network to be a significant barrier to entry. The process is described as being highly complex, and difficult for non-engineers to navigate.

“If you don’t tick every box correctly, the DNO will send you to the back of the queue and stop the clock on your application. For a lot of people, because they are unfamiliar with the process, there is a risk that the clock times out, they have to reapply and they just give up,”

– Mark Thomas, director of G59 Professional Services.

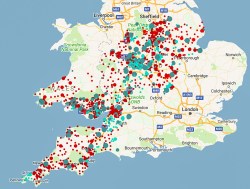

As DNOs transform into DSOs, they are increasingly interested in how DSR can help them to avoid network reinforcement. Western Power Distribution has recently created an online map showing where connections are more viable than others, and conference delegates agreed that a nation-wide map would be useful.

Delegates also observed that where their operations cover multiple local networks, they need to engage with each DNO separately, creating significant additional work for them.

UK Power Networks is launching a tender for 35 MW of flexibility in the East and South East that will allow it to increase exports (generate) or reduce imports (consume less) at times of high demand. It will award both availability and utilisation payments subject to minimum 500kW of flexibility, which can be aggregated across multiple sites. Delivery is required for between two hours and five hours to manage evening peaks in some locations, and morning and evening peaks in others.

Western Power Distribution has launched a DSR trial in the East Midlands, focusing on minimising the inconvenience to providers, and maximising the revenue streams flexibility they can stack. In order to actively manage constraints, WPD would like to be able to notify participants to reduce power or increase generation with signals a week ahead of time.

An “arming fee” would be paid to DSR providers when the initial nomination is made, which will guarantee an acceptable level of income. Closer to delivery, WPD would retain the flexibility to call or not call on the DSR provision as needed, and if it is called, a utilisation fee would also be paid.

The structure of this service has the potential to put the DSO in direct competition with aggregators, and there is a real question as to whether over time the role of aggregators might be subsumed within the activity of the emerging DSOs. While this may be a natural development, it opens DSOs to the same conflict of interest concerns that arise in relation to National Grid as owner and operator of the transmission system. It may be that as Ofgem considers whether an independent system operator is needed, it should apply the same thinking at the distribution level.

“I think generators, I&C consumers, the people who own flexibility, will in the future potentially contract directly with DNOs and/or the system operator,”

– Eamonn Boland, Baringa Partners

Questions are also being asked about how Project TERRE, an EU project to create a pan-European flexibility market, may impact the provision of DSR services in the UK. The ultimate goal of the project is to a create a central platform that enables close to real-time exchange of balancing products between European transmission system operators, including National Grid, which is planning its re-design of balancing services on the same timetable.

What next for DSR?

A raft of regulatory changes is in the pipeline which is likely to impact the DSR

- In June, Ofgem confirmed plans to cut triad payments: they are set to fall by a third next year, disappearing almost entirely over three years;

- In August, Ofgem launched a wide-scale review of network charging which are likely to impact DSR business plans and revenues;

- This summer, government and regulator jointly published a Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan, setting out plans to make flexibility markets more accessible, simplify metering requirements and remove regulatory barriers for storage, although the details, particularly around timing are yet to be published;

- Last September, Ofgem agreed a change that will flatten network charges, meaning that business cases predicated on avoiding red band charges may need to be re-visited;

- National Grid has recently announced plans to change the way it procures balancing services – further details are expected later this year;

- Ofgem is also working on plans to allow aggregators to access the balancing and wholesale markets;

- Legislation is also coming in to limit running hours and emissions limits from back-up generation to address the issue of the success of diesel generators in the capacity market.

These changes present significant uncertainty for DSR providers, but for the most part they are aimed at removing barriers to entry and providing a wider range of revenue streams.

Some companies such as Marks & Spencer report that their DSR investment is starting to pay off, with consumption reduced by 10% over the past year, in part due to DSR activities. The impact of capacity market costs likely to provide new incentives for consumers to explore DSR provision. Smartest Energy is forecasting that the amount re-charged to users to pay for the capacity market will rise from almost nothing last winter to £41 /MWh for winter 2017, to £110 / MWh for Winter 2018 (for the winter peak periods). Inenco has similar forecasts.

Wholesale commodity costs are likely to become increasingly volatile with more price spikes, due both to lower capacity margins and reforms to imbalance arrangements…cashout prices have exceeded £1,000 /MWh on a number of recent occasions, as unplanned outages stressed the system. This provides further incentives for companies to actively manage their consumption, and explore ways of earning revenues from load shifting.

“We have already seen how little it takes to push the system to periods of high volatility in the wholesale prices and balancing mechanism cashout prices. In our modelling going forward… we continue to see similar, if not the exact same levels, of volatility in the wholesale market and the balancing mechanism,”

– Eamonn Boland, Baringa Partners.

The economic picture for DSR is changing. Some sources of revenue are declining or even disappearing, while new opportunities are opening up. More work needs to be done to remove entry barriers, and in particular the practical barriers to DSR provision: the process for grid connections could and should be streamlined, and creation of standards for aggregator equipment and software should be explored to make it easier for DSR providers to change their RTM provision.

As Ofgem and National Grid progress their various workstreams outlines above, attention should be paid to creation of stable revenue streams and contracts of appropriate duration that will allow companies to raise or allocate finance to projects that enable DSR participation.

What’s clear is that as bills rise and energy prices become more volatile, the costs of doing nothing will only increase.

Thanks Kathryn for this summary and analysis of the ongoing changes to the ‘rules’ to what I think is the industrial use of electricity. This is the first time I have seen a little of what changes are proposed. I have two comments:-

1 – Ever more complex and fluid rules as to who gets ‘the money’.

2 – All this seems to arise from the introduction of ‘renewables’ that I consider less competant to deliver electricity to the standards we are accustomed to. Introduced by law to address a non-existent problem with CO2.

Nick.

I think increased complexity is inevitable as intermittency increases and inertia falls. Perhaps as the costs of all this grow, people will look again at the drivers, but unfortunately the idea that CO2 is to blame is now ingrained.

I agree that complexity and intermittency are increasing and system inertia is falling. I am confused by your second sentence.

..”but unfortunately the idea that CO2 is to blame is now ingrained”..

Please re-phrase this.

I consider that the general public is unaware of the extent of the costs of lavish support for ‘renewable’ sources of power. This drive for renewables is an effort to reduce CO2 generation. Maybe this is the ingrained idea you refer to? I certainly think demonising CO2 is the fundamental driver for all these power system changes.

We all will be paying twice for an unnecessary revolution in our electricity

bills. First to provide all the wind and solar electricity generators, then again to make up for all the attributes they do not provide.

Thanks again for your insightful posts.

Nick.

Hi Nick,

That’s exactly what I meant…the public (and policymakers for that matter) believe that CO2 is responsible for climate change and therefore we need renewable power. The costs of this renewable power is then obscured, so that while the public sees bills rising, they do not in general understand that this is a result of decarbonisation policies.

Everyone is now celebrating the low cost of offshore wind, conveniently forgetting that the costs of managing intermittency and low inertia are rising significantly (which is the subject of my next post!)

Kathryn

Thanks for the clarification.

I look forward to your next post.

Nick.