Calls are growing for the UK electricity system to be managed by an independent system operator (“ISO”) whose activities are separate from the ownership of the wires themselves. Such a change would require nationalisation of the system operation activities of National Grid, and the creation of a new regulatory framework for the electricity system.

This would represent a major and disruptive change to the structure of the market, and would potentially be expensive, so the increasing calls for such a change suggest that some consider the costs of inaction would be higher.

The energy system is undergoing a major transformation, driven by decarbonisation, which is changing the physical nature of the system. As I have discussed in previous posts, the migration from large centralised units of conventional generation to smaller, decentralised, and often non-dispatchable generation is fundamentally changing the physical structure of electricity delivery.

System operators now face multiple challenges relating to intermittency, reduction in inertia, and managing the existence of large amounts of embedded generation which is difficult to forecast since it is not generally metered on a half-hourly basis.

Impact of “connect and manage”

Part of the problem is due to the way in which new generation has been added to the network. When the first wind projects started to be added in the first decade of this century, developers faced long delays in getting grid connection which inhibited the overall rollout of renewables on the system. To address this, the “connect and manage” transmission access regime was introduced in 2011, which offered generators connection dates ahead of the completion of wider system reinforcements.

New technologies are emerging that can help manage these challenges, but these are inhibited by market rules that are oriented around provision of capacity. For example, there are no specific regulations covering storage, so typically it is treated as generation. Storage could remove the need for network reinforcement, but being classified as generation, neither transmission nor distribution system operators are permitted to own storage assets.

DSR is a very cost-effective way of reducing reinforcement needs, but again there is a lack of route-to-market opportunities that inhibit its growth (as described in my post on turndown DSR).

The bias towards capacity in the current governance framework was very apparent in the evidence before the final sessions of the Energy and Climate Change Committee quoted in my previous post, and is also the subject of various academic teams examining the energy transition. Catherine Mitchell at Exeter University’s Energy Policy team says of the energy transition:

“…the most fundamental challenge in this transformation is not technical, but rather one of governance, and specifically inertia within governance”

This issue of inertia is aggravated by the significant complexity of the governance framework, as explained in depressing detail by this Government review where market participants struggle to even identify all the regulations with which they must comply. This clearly discriminates against new entrants that lack the large regulatory compliance functions of the big, established market participants.

Impact of conflicts of interest

In its Low carbon network infrastructure report, the Energy and Climate Change Committee examined the role of National Grid as the system operator and identified two clear conflicts of interest:

- “asset padding” whereby National Grid has the power and incentive to encourage physical infrastructure development and then profit from it, since National Grid is in a position to make recommendations as to the levels of transmission capacity required; and

- the ownership of interconnectors, where National Grid owns and operates interconnectors, which are used as backup in times of system tightness, and are eligible to participate in the capacity market, creating another incentive for National Grid to boost its capacity recommendations.

National Grid argues in the first case that the price control mechanisms that cap overall expenditure would incentivise against such a strategy, however others highlight that while that may the case with each individual period, a near term overspend can encourage high caps to be set in future periods. In relation to interconnectors, National Grid says that it has strict Chinese walls separating its interconnection and system operation businesses, which limits the risks posed by this apparent conflict of interest.

However, it is clear that capacity is strongly favoured in the UK electricity market, above flexibility or demand reduction, and new technologies are suffering as a result. Whether this bias is due to poorly managed conflicts of interest, or excess conservatism, or some combination of the two is difficult to determine, but the outcome is that both storage and DSR face unnecessary barriers to market entry.

The Committee found that small-scale generators faced long and uncertain queues to connect to the National Grid and recommended a review of connection costs, and that regulatory barriers were holding back development of both storage and DSR technologies:

“The glacial pace with which regulation is adapting to storage may be a greater impediment than any technological immaturity: overcoming regulatory barriers to storage has become a dominant theme of this inquiry.”

Overall, the Committee concluded:

“We recommend creating an Independent System Operator (ISO). Despite strong efforts by National Grid itself and Ofgem to mitigate the potential for conflicts of interest, it seems intractable and growing.”

Noting that the Independent System Operator model works well elsewhere, particularly in the US.

The report also highlighted the need for clear government policy on the evolution of Distribution Network Operators, with their very passive approach to system management, to Distribution System Operators (“DSOs”) – a change for which the need is widely acknowledged, but there is no current delivery plan.

The National Grid spoke out against the report’s findings, and is quoted in The Guardian saying the recent report by Andrew Adonis, from the National Infrastructure Commission, found no sign that the grid had up till now had negatively affected consumers.

“There is little evidence that an independent system operator model would provide any benefits that would justify the cost to households, potential disruption to much of the energy sector, and the risks to security of supply such uncertainty could create.”

However that same report recognised that there are conflicts of interest between the different roles carried out by National Grid, and that while creation of an independent system operator should not be a near term priority, Ofgem needs to encourage National Grid to develop new ancillary services frameworks that will allow new technologies such as storage and demand side response to participate more easily, and that there must be open competition for these services.

How would an independent system operator work?

Catherine Mitchell’s work in this area advocates the following set of principles for institutional reform for a sustainable, secure and affordable energy system:

- Consumer-centric

- Facilitating local markets

- Open and transparent access to data

- Greater co-ordination

- Long-term political stability

- Transparency and legitimacy in policy making

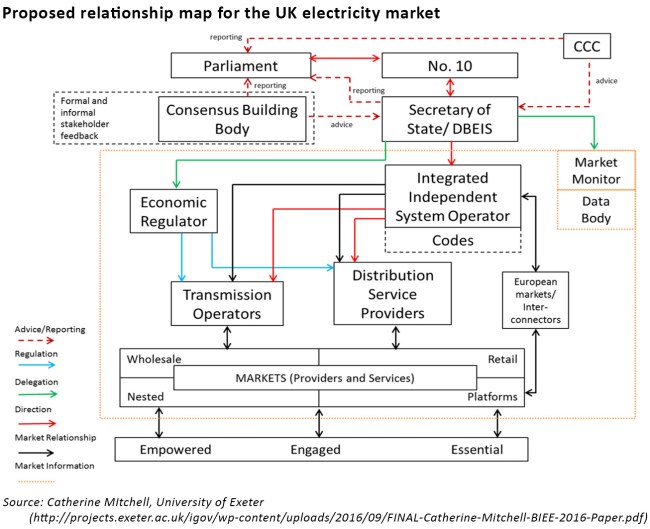

The current map of institutional relationships in the electricity market is both complex and conflicting (and difficult to read!):

Mitchell proposes a new framework that re-defines the social contract between energy market participants and consumers, and goes as far as to suggest a specific “social licence” to underpin this relationship and restore consumer confidence in the various actors in the market. That such a proposal is made highlights the counterproductive political narratives where energy providers are both derided as greedy and dishonest, while at the same time placed at the centre of various market initiatives (smart meters, “green deal” home improvements etc)….surprise is then expressed at the low consumer acceptance of those initiatives.

She goes on to recommend creation of local markets, with DSOs (which she calls Distribution Service Providers) at their centre, providing platforms for local markets and network services, and where producers and consumers can chose to transact either in the local pool or the national wholesale market.

A key feature of the IGov model developed by Mitchell is the creation of an Independent (Integrated) System Operator – “integrated” as it would work across all segments of the energy system ie gas, heat and transport as well as electricity, and having a view across transmission and distribution. Crucially, the IISO would be separate from the transmission operator, ie the building and maintenance of the physical network would be separate from the operation of the system.

The IISO would take on the system operator roles currently played by National Grid in electricity, including half-hourly scheduling, frequency management, reserve management and ancillary services, although these would be increasingly shared with the DSPs acting at the local level. In order to avoid conflicts of interest, the IISO would be state-owned.

With evidence from the industry that the current framework is not fit for purpose, and evidence from the National Audit Office that energy costs are not being well controlled, there is a strong case for responding to fundamental market change with a fundamental re-design of the regulatory and governance frameworks that underpin it, including the creation of an independent system operator.

While any major change will inevitably cause disruption, it is not necessarily greater than the disruption than can result from lack of action. Continuing the layering of subsidies and failing to adequately manage the conflicts of interest will not deliver a secure, low cost, decarbonised energy system, and indeed risks failing to deliver on each of the key objectives of UK energy policy.

Leave A Comment