This week has seen the failure of three more energy suppliers: Pure Planet which supplies gas and electricity to around 235,000 domestic customers, Colorado Energy with around 15,000 domestic customers, and Daligas with around 9,000 domestic and non-domestic customers. This new round of closures affects just over a quarter of a million consumers, and brings the total number of supplier failures this year to 15, with 13 since August. More are likely.

What has received less publicity outside of the energy markets is the announcement that gas shipper CNG is closing. This is the first time a shipper has exited the market which provides third party shipping services to other parties – CNG acts as a shipper on behalf of 18 energy suppliers. There is no equivalent of the SOLR process for shippers, leaving many in the industry wondering how those suppliers will now manage their gas shipping needs.

“…one gas shipper, that provides wholesale gas to 18 utility companies, about to exit – that could cause a domino effect,”

– Dale Vince, founder, Ecotricity

CNG has written to its customers advising them to move quickly to find an alternative provider.

What is a shipper?

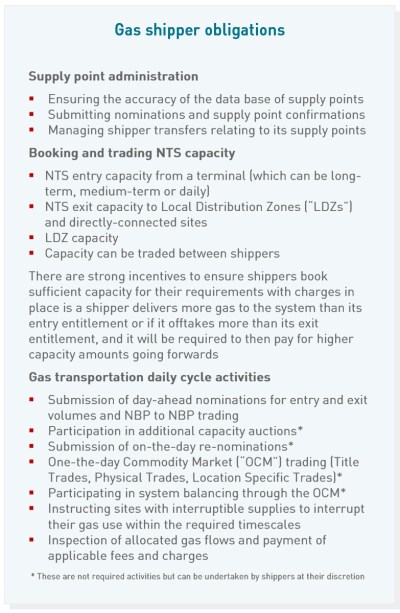

A gas shipper manages the logistics of gas on the national transmission system (“NTS”). The difference between a shipper and a supplier is that whereas the supplier sells gas to end consumers, the shipper arranges the physical logistics of transporting the gas to that consumer. This involves booking entry and exit capacity and managing imbalances.

Unlike the electricity market which is balanced every half hour, gas markets are balanced daily due to the ability to store varying amounts of gas within the pipes themselves by varying the pressure of the gas. This storage capacity, known as “linepack” has limits, but it provides a level of flexibility which is not possible in the electricity markets, allowing for a wider balancing window.

Unlike the electricity market which is balanced every half hour, gas markets are balanced daily due to the ability to store varying amounts of gas within the pipes themselves by varying the pressure of the gas. This storage capacity, known as “linepack” has limits, but it provides a level of flexibility which is not possible in the electricity markets, allowing for a wider balancing window.

Most larger gas suppliers perform their own shipping activities in-house, but smaller suppliers have increasingly sought third party providers to perform the physical logistics on their behalf. Shippers must hold a shipper licence, and the process of becoming a shipper is quite involved, typically taking 4-6 months. Those suppliers using CNG as the shipper will be buying gas from CNG and paying it both for the gas and for all the steps required to deliver that gas to their customers.

CNG procured its gas from Glencore which holds a share in the company, but the gas can also be bought from upstream producers delivering to an on-shore terminal, LNG sellers delivering to a specific NTS entry point (at the re-gasification facility), holders of stored gas in one of Britain’s salt-cavern storage sites, or from another shipper in a title transfer transaction.

As in the electricity networks, transmission and distribution charges are imposed by network operators, and balancing costs are shared between system users.

What went wrong for CNG?

Reading its last published accounts for the year to October 2020 (signed in June this year), it’s clear that CNG has been in difficulties for some time, undergoing a re-structuring in 2020 that appears not to have been successful in the face of the higher market risks this year. Three of its seven directors also resigned in September, which was a warning flag for anyone following the company’s progress. Trade debtors grew by £18 million in 2020, and average debtor days increased from 27 days in 2019 to 42 days in 2020 – a warning sign that it was finding it harder to meet its payment obligations. At the same time, trade creditors fell by around £30 million, squeezing working capital.

CNG entered into a six-year, £35 million loan agreement with Glencore, which it expected would “provide long term security for the Group”, alongside a new structured supply agreement which extended existing credit facilities for gas supplies to £30 million.

Given the warning signs evident in the accounts, it is reasonable to wonder how the company’s auditors managed to be comfortable to sign off the accounts on a going-concern basis when just four months later the company is going out of business.

Why does this matter?

It is unclear how managed this exit by CNG is, but its customers will now need to replace their CNG gas contracts with other providers at current market prices, losing any fixed price arrangements they had with CNG, and even potentially the collateral they had provided to CNG to cover their positions.

If that is the case it will have a severe and potentially unaffordable liquidity impact on those suppliers, who are generally smaller and less well capitalised. Indeed, focusing on this client base is likely to be the cause of CNG’s problems as some of its customers have gone bankrupt, leaving unpaid bills. Avro Energy, which collapsed last month, with 580,000 customers was reportedly one of CNG’s clients.

“While the precise consequences for each company will depend on their circumstances, they will all face the challenge of finding a new provider in what are obviously very challenging conditions,”

Energy UK

It isn’t entirely clear how the physical gas system impact will be managed between the exit of CNG and suppliers finding a new shipper. Their customers will still be using the same gas, but now there will be no corresponding purchases or exit capacity bookings. Usually if a system user consumes gas without having nominated the necessary volumes and capacities, they effectively purchase this gas from National Grid at the System Marginal Buy Price as a delivery of “un-authorised gas” under a system clearing contract.

But these suppliers are not necessarily “users” of the system if the supply points were registered with CNG, so there are questions over how those volumes will be allocated appropriately. This situation has not arisen before so it’s unclear if the Uniform Network Code which governs gas market logistics contains any provisions for it.

In addition to its third party shipper services, CNG has a supply business with around 40,000 small and medium-sized businesses. The company is reportedly seeking a trade buyer for its customer book, but failing that, this part of its operations would be covered by the SOLR process.

The consensus in the market seems to be that many of the 18 small suppliers for who CNG provides shipper services will now fold since even if the CNG exit is managed smoothly and their collateral is recovered, they will not be able to replace their hedges at affordable levels. This would resolve the issue of allocating gas imbalances since the customers of these suppliers will be allocated to a SOLR which almost certainly carries out its own shipping operations.

But it still leaves Ofgem with a headache. Organisations like CNG facilitated market entry for smaller suppliers without the need for them to build many of the operational processes that had historically been needed. In recent years, Ofgem has recognised that this capital-light supplier model created un-acceptable risks for consumers and began to tighten entry requirements, and many of these companies are now failing.

It essentially means that suppliers need to be well capitalised and have both the financial and operational means to carry out their own physical logistics, procurement and risk management. This will raise barriers to entry and limit competition. Somehow the tension between a political desire to offer consumers wider choice and the need to recognise market realities needs to be reconciled.

To what extent has OFGEM contributed to the problems with electricity and gas disruption we have recently seen? Whilst consumers understand the benefits of having more suppliers, the new entrants seem to operate on the basis of tempting customers with low tariffs but not having robust policies and finances which means that they rapidly have to increase charges. I believe that suppliers are licensed by OFGEM so perhaps this needs to be tightened up

If the current regimen for licensing continues, the public will lose confidence in switching.