Power Purchase Agreements (or “PPAs”) have been around for a long time, as agreements between market participants for the offtake of electricity from generating facilities. However, the past few years have seen the rise of the so-called “Corporate PPA” where companies whose business is not related to energy are procuring the electricity the use in their business directly from generators, often in order to demonstrate environmental credentials.

The ability to source electricity directly from renewable sources, together with achieving long term price certainty, has become a key business objective for corporates who are becoming increasingly pro-active in their procurement strategies. This has led to strong growth in corporate PPAs in recent years, particularly in USA and LATAM, with major players including Google, Apple, Amazon, Unilever, Microsoft and others. The UK has seen deals from BT, M&S, Nestle, McDonalds, HSBC, Lloyds, and Nationwide.

As wholesale prices are becoming more volatile, and prices for end users are inflated by the effects of environmental policies, interest in corporate PPAs is growing among both corporate buyers and renewable generators. According to Ronan Lambe, senior associate at law firm Pinsent Masons, the growing popularity of corporate PPAs is the culmination of two separate trends:

“Energy use is a key focus in many corporate boardrooms. Large energy users have always had reduction of energy costs at the front of their minds but are now increasingly under pressure to demonstrate to shareholders that they are taking steps to procure that energy in a sustainable way.

Secondly, in a low or no subsidy environment developers of renewable energy projects are under pressure to cut costs and innovate in order to survive.

Corporate PPAs can offer a solution to both parties: providing a useful hedge for the large energy user against increases in power prices and short term price volatility while providing the project developer with a vital long term route to market for the power it produces, underpinning the economics of the project.”

Corporate PPA structures

There are a number of possible corporate PPA structures (see below) each with their own benefits and drawbacks, that can be contracted with new energy projects or existing generation.

In its simplest form, a PPA is simply an agreement for the purchase of power at an agreed price or price reference, however it is usual for PPAs to include both gain sharing arrangements and some degree of operational and risk sharing. Power purchase agreements may have a variety of forms depending on the nature of the underlying asset – primarily whether it’s a new-build project or existing plant, and whether it is transmission or distribution connected.

- New-build PPAs can have long maturities (10-year deals are common), however there is less appetite among traditional buyers for fixed price structures or price floors, and these would only be offered for shorter periods if at all.

- Income and risk-sharing arrangements are determined by the location of the asset in the system:

- For transmission-connected assets the off-taker may make dispatching decisions and enter the asset into the balancing and ancillary services markets, as well as managing balancing risks;

- For distribution-connected assets the off-taker might manage dispatch to exploit embedded benefits.

It is essential to ensure that the specific principles of the activities and risk-sharing are properly defined, and that the benefits can be audited to ensure gains are distributed appropriately. Appropriate IT systems capable of managing complex settlement processes are required.

“A corporate PPA, like any PPA, provides unit energy price surety for the length of the term, which benefits predictability of returns, and thus the business case of the project. From experience, the involvement of the corporate party early in the development process (i.e. before the wind farm is operational) allows for the weight of the corporate PPA to provide maximum benefit in ensuring more informed project financing.

Besides the finance-related benefits, we also see a desire from the corporate world to be greener and have their brand associated with sustainability, and PPAs are an attractive way to meet that as an alternative to direct investment in renewable assets,”

– Vicky O’Connor, Senior Consultant at K2 Management

Corporate PPAs are PPA transactions between a generator and a corporate end-user – generally a company with large electricity procurement needs. As the corporate buyer is unlikely to be either physically connected to the generating asset, or a signatory to the Balancing & Settlements Code, a BSC Party or Licenced Supplier is needed to manage the physical market operations of the arrangements.

The simplest way to deal with this is through a synthetic corporate PPA, where all of the physical operations are managed by a supplier, and the generator and corporate buyer enter into a contract for difference, which effectively secures a fixed price for the power for both parties. In a sleeved corporate PPA, the corporate buyer enters into a direct PPA with the generator, and a back-to-back PPA with the supplier.

In the UK market, the synthetic PPA approach has been championed by Marks & Spencer plc, whose multi-award winning “Price Guarantee Agreement” was a relatively simple form of contract for difference that was rolled out on over 20 projects. Aside from this, the most common form of PPA in the UK has been the back-to-back, sleeved PPA structure, despite their greater complexity. This can mean that corporate buyers find themselves engaging in complex energy-market based negotiations to ensure they are not left managing any risks outside their usual competencies.

Longer fixed price durations can be possible than for corporate PPAs than wholesale PPAs, but the creditworthiness of the buyer is key, particularly if the PPA is being used to support the project finance for the asset.

Direct or private wires PPAs are a particular type of corporate PPA where the generator has a physical connection both to the customer through private wires, and to the grid. A direct physical connection between the generator and the corporate buyer saves on grid costs, although the upfront capex costs are higher, and connections greater than a few kilometres become prohibitively expensive.

A parallel PPA arrangement is required with a licenced supplier to deal with surplus volumes not required by the customer, and also so the supplier can act as a back-stop buyer in the event the customer becomes unable to fulfil its obligations under its PPA (otherwise the generation plant would have to stop operating).

The electricity price achieved by the generator is typically higher than for either wholesale or sleeved corporate PPAs, but the process of implementing the transaction is complex: requirements include a willingness on the part of the parties to enter into complex arrangements with high transaction costs, the customer must be credit worthy, the physical location must be suitable for the direct connection to be made, the co-operation of local DNO/TSO is needed for backstop arrangements as there must be sufficient capacity on local grid to take full offtake if needed.

Corporate PPA volumes growing rapidly

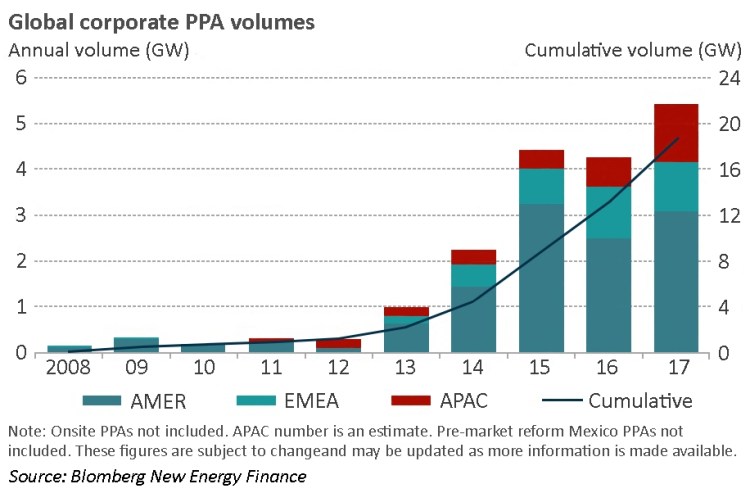

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, corporations signed record volumes of power purchase agreements for green energy in 2017. This increase was driven by sustainability initiatives and the increasing cost-competitiveness of renewables. A total of 5.4 GW of clean energy contracts were signed by 43 corporations in 10 different countries, up from 4.3 GW in 2016 and the previous record of 4.4 GW in 2015.

BNEF expects this trend to continue in 2018, driven by the environmental commitments made by companies, particularly those who signed onto the RE100 campaign in 2017. RE100 brings together corporations pledging to source 100% of their electricity from renewables at some date in the future – at the end of 2017, RE100 had 119 members. In 2016, these companies consumed 159 TWh of electricity globally, almost the same amount of electricity as consumed in the whole of Sweden.

“The growth in corporate procurement, despite political and economic barriers, demonstrates the importance of environmental, social and governance issues for companies. Sustainability and acting sustainably in many instances are even more important, for the largest corporate clean energy buyers around the world, than any savings made on the cost of electricity,”

– Kyle Harrison, corporate energy strategy analyst at BNEF

Most of the activity in 2017 took place in the United States, where 2.8 GW of corporate PPAs were concluded – a 19% increase on 2016. The most notable of these deals was Apple’s 200 MW PPA with NV Energy to purchase electricity from the Techren Solar project, the largest agreement ever signed in the US between a corporation and a utility.

Europe saw over 1 GW of new corporate PPAs being signed, 95% which were connected with projects in the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden where policy mechanisms allow developers to secure subsidies, while also giving corporations the ability to receive certificates to meet sustainability targets. The largest deal was aluminum producer Norsk Hydro’s commitment to purchase most of the electricity from the 650 MW Markbygden Ett wind farm in Sweden, between 2021 to 2039.

Corporate PPA activity also began to emerge in new markets including Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Egypt, Ghana, Namibia, Panama and Thailand.

Energy markets are going through rapid changes, alongside which the risk of higher wholesale price volatility and the impact of environmental policy costs is leading to a more proactive approach to energy management by corporate consumers. As well as engaging in dynamic management of load patterns, and providing demand-side response services to network operators, large energy users are increasingly contracting directly with generators for their procurement.

This provides additional routes to market for generators, and the ability for corporate consumers to demonstrate environmental credentials, which are seen as an important brand differentiator. This trend is likely to continue, however companies on either side of the transaction need to be mindful of regulatory changes than can disrupt both the mechanics and economics of such deals, especially for contracts with longer tenors.

I have often wondered how an energy user can claim they only use renewable sources- as electrons are not colour coded! I considered that some form of accounting and contracting was required. Now we see how complex the variations are that are needed to prevent(?) gaming of the system and conning the general public.

Nick.

ps – I don’t understand the post in detail. I am sure many professionals will though.

It would be informative to see how much renewable energy is generated and how much is supplied to domestic customers.

Hi Nick,

This is one of the ways to “buy green”. It can also be done in a completely virtual way buy purchasing green certificates (Renewable Guarantees of Origin or REGOs). Ofgem issues REGOs to renewable generators and these can be sold to suppliers who need to demonstrate that they source a certain portion of their electricity from green sources.

Large consumers can buy renewable energy directly from the generator under a PPA, bundled with REGOs, or they can buy the energy and REGOs separately. Smaller consumers can opt for a “green tariff” from their supplier, which is likely to be backed by REGOs. Some people call this “green-washing” since the actual electricity supplied might have come from non-renewable sources, but by buying REGOs the supplier has contributed to subsidising renewable generation.

You can see how much renewable energy is being generated here and Ofgem also has some data. I’m not sure about the Ofgem number, but the gridwatch figures relate to transmission-connected generation, so embedded renewable generation (ie connected to distribution networks) will appear as a reduction in demand. I’m not sure how much ends up with domestic consumers rather than the I&C segment though.

Kathryn