December saw the publication of the long-awaited energy white paper, which built on Boris Johnson’s 10-point energy plan. In 170 pages, the white paper describes in high level terms how the Government plans to achieve its 2050 net zero carbon target, but provides little additional detail to the 10-point plan. Instead there is a long list of plans and strategy papers which are promised over the coming year, which will presumably provide a clearer view of the Government’s roadmap. There will also be a lot of consultations on various aspects of the country’s energy systems and governance.

The white paper says that “the shift to net zero will affect us all”, and attempts to set out the changes which will be required. Emissions will be reduced through replacing gas with electricity for domestic heating, and by better building insulation, and by ending the sale of petrol and diesel cars and vans.

The white paper says that “the shift to net zero will affect us all”, and attempts to set out the changes which will be required. Emissions will be reduced through replacing gas with electricity for domestic heating, and by better building insulation, and by ending the sale of petrol and diesel cars and vans.

Alongside this will be a transition to cleaner fuels such as hydrogen, and emissions from power generation and industry will be captured. Consumers will use smart meters and a range of smart appliances, backed by new smart tariffs, to control their energy use and manage bills “running the washing machine or charging the electric vehicle when demand is low and electricity is cheap, even selling surplus power back to the grid at a profit.”

The white paper states that affordability will be key, and that the falling costs of renewables and in particular, offshore wind mean that bills will remain affordable. A “major push” on improving the energy efficiency of homes will allow households to significantly reduce demand and save money on their bills.

Finally, the transition will create jobs and benefit the economy.

“The global markets for low-carbon technologies, electric vehicles and clean energy are fast growing: zero emission vehicles could support 40,000 jobs by 2030, with exports of new technologies such as CCUS having the potential to add £3.6 billion GVA by 2030,”

– Energy White Paper

The white paper goes on to discuss seven areas in more detail: Consumers; Power; the Energy System; Transport; Buildings, Industrial Energy and Oil & Gas.

Consumers are real people and not the affluent energy enthusiasts of the white paper

The Government has three key priorities for consumers:

- Creating a fair deal for consumers

- Protecting the fuel poor

- Providing opportunities to make savings on energy bills

“Consumers can be rewarded for playing a bigger role in our energy system. There are plenty of ways to save money, from installing energy saving measures to making the most of new technologies, such as batteries, heating controls or smart washing machines and dishwashers. Consumers can also generate their own electricity through roof-top solar panels, store it in batteries, and even sell any excess power back to the grid to generate a profit at times of higher demand,”

– Energy White Paper

This describes a somewhat utopian view of consumers as sufficiently affluent and educated to invest in energy assets and sufficiently motivated to optimise them. In reality, that may describe the people who wrote this white paper, but it ignores the circumstances of millions of people on low incomes, or with low levels of literacy, or low levels of computer literacy; people who don’t own their own homes, or even their furniture and appliances.

The Government recognises this to a certain extent, pointing out that more active consumers could potentially avoid paying for shared network assets by moving partly off-grid, and that more than half of consumers remain of default tariffs despite almost all knowing about the possibility of switching, but it’s solutions are rather superficial and fail to reflect the sheer size of the changes consumers will be forced to undertake in order for net zero to be achieved.

These changes are described in National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios, and they will be significant. Consumers will need to make radical changes to their homes, replace their appliances, install new heating systems, replace their cars with new, low/zero emission alternatives, get to grips with the fuelling needs of their new cars, and get to grips with the range of new types of tariffs and energy products that will emerge. They may, if the FES are to be believed, need to hugely reduce the amount they travel.

When 7.5% of British adults has never used the internet and a further 6% are considered “lapsed” internet users (ie people who have not used the internet for at least the last 3 months), many are not equipped for this challenge. That half of energy consumers have not switched despite knowing they could indicates that energy simply is not a priority for a significant portion of the population.

To address this, the Government is considering the introduction of opt-in switching, where consumers are offered an improved tariff once their initial contract ends. Trials have shown that this process, which simplifies the switching process and provides a degree of independent support, incentivised a higher degree of switching, although it should be noted that of the 1.1 million customers in the various trials run by Ofgem, just 94,000 switched which is around 8.5%. Opt-out switching is also to be considered, where consumers are automatically switched to another tariff unless they actively choose not to be. It remains to be seen whether reducing or removing consumers’ agency will actually be to their benefit.

There will also be consultations on whether the supplier thresholds in the ECO and WHD schemes should be removed – on the one hand these thresholds reduce barrier to entry for new suppliers but on the other hand they create market distortions. Of course, my preference would be for these schemes to be removed from suppliers altogether, and for suppliers to concentrate purely on supplying energy, and developing innovative tariffs that will support the energy transition.

There will also be consultations on whether the supplier thresholds in the ECO and WHD schemes should be removed – on the one hand these thresholds reduce barrier to entry for new suppliers but on the other hand they create market distortions. Of course, my preference would be for these schemes to be removed from suppliers altogether, and for suppliers to concentrate purely on supplying energy, and developing innovative tariffs that will support the energy transition.

The Government will assess what market framework changes may be needed to support a variety of business models such as peer-to-peer trading, energy as a service, or the bundling of different utilities, such as water and energy. There will be a consultation by spring 2021 on regulating third parties such as energy brokers and price comparison websites, which are currently unregulated.

In this regard, the energy white paper does not go far enough since it mentions protecting households and micro-businesses, yet arguably all consumers should be protected. Looking to the financial markets as a comparator, we can see that very few categories of consumers are not afforded significant levels of protection – simply being a large user of financial services or having a lot of employees is not enough for an entity to be classified as a “Professional Counterparty”, yet in the energy markets, using a large amount of gas or electricity, or simply having a lot of staff means that there are almost no regulatory protections.

Finally, there are proposals to regulate smart appliances to set standards around interoperability, data privacy and cyber security. This is important since smart appliances provide a route for hackers to compromise local computer networks and even the physical security of consumers for example where criminals use smart appliances to spy on consumers in order to choose the best time to burgle their home.

Buildings represent a major challenge to achieving net zero

Buildings are the second largest contributor to UK emissions, with 90% of homes using fossil fuels for space and water heating and cooking. Two thirds of homes have an Energy Performance Certificate (“EPC”) rating of D or worse. As National Grid suggested in its Future Energy Scenarios – pretty much every home in the country will need to make changes to its energy sources and fabric in order to achieve net zero. This will be a huge challenge, both logistically and in terms of consumer acceptance.

The white paper emphasises the benefits of insulation and energy efficiency, and it is right to do so, but there needs to be a huge health warning here: no-one knows what actually makes for an energy efficient building. That sounds controversial, but research carried out in 2017 by the Professor David Coley of the University of Bath demonstrated that the professionals that model building energy performance were no better than the man in the street at predicting which features would be best at reducing energy use. Other studies have illustrated a phenomenon known in the construction industry as the “Performance Gap” where the energy consumption of a building in use can be an order of magnitude higher than was expected in the design phase.

The white paper emphasises the benefits of insulation and energy efficiency, and it is right to do so, but there needs to be a huge health warning here: no-one knows what actually makes for an energy efficient building. That sounds controversial, but research carried out in 2017 by the Professor David Coley of the University of Bath demonstrated that the professionals that model building energy performance were no better than the man in the street at predicting which features would be best at reducing energy use. Other studies have illustrated a phenomenon known in the construction industry as the “Performance Gap” where the energy consumption of a building in use can be an order of magnitude higher than was expected in the design phase.

A slew of consultations is being carried out around improvements to buildings, with new standards being developed, but if the Performance Gap is not addressed then these will not deliver the desired results. Language in the white paper around the modelled energy performance of buildings is worrying, since the research tells us that the modelled performance correlates poorly with the actual performance – the Government needs to move away from reliance on models and require the use of actual performance data, beginning with actual energy consumption, and moving towards actual emissions analysis.

A slew of consultations is being carried out around improvements to buildings, with new standards being developed, but if the Performance Gap is not addressed then these will not deliver the desired results. Language in the white paper around the modelled energy performance of buildings is worrying, since the research tells us that the modelled performance correlates poorly with the actual performance – the Government needs to move away from reliance on models and require the use of actual performance data, beginning with actual energy consumption, and moving towards actual emissions analysis.

Making changes to the fabric of buildings to improve energy efficiency or introduce new energy assets such as solar panels, batteries and EV charges is significantly easier in owner-occupied properties than those that are privately rented. In rented properties there is a conflict between the tenant who pays for the energy used, and the owner who pays for the property itself. This is further complicated in rented leasehold properties where the landlord is often not the owner of the building. BEIS is set to publish a dedicated Heat and Buildings Strategy in early 2021 which will set out in detail the suite of policy levers that will encourage consumers and businesses to make the necessary transitions.

The white paper sets out a range of policy measures to support remedial work to improve the energy efficiency of buildings, but these cover a relatively small number of properties and some of the targets are strongly caveated, eg “all rented non-domestic buildings will be EPC Band B by 2030, where cost-effective”…who decides what is cost-effective and who checks?

A £1.5 billion voucher scheme offers homeowners and landlords a voucher covering up to two thirds of the cost of upgrading energy performance, to a maximum of £5,000, with up to £10,000 being available for low-income households, with no contribution required. Low-income households can also benefit from the £500 million of the Green Homes Grant. “The schemes could enable more than 600,000 homes in England to be more energy efficient, saving these households up to £600 year on their energy bills.” This statement is problematic in two ways: the first is that a £5,000 investment for 600,000 homes would cost £3 billion, so the scheme assumes most projects will be much smaller than this; and the second is that 600,000 homes is just 2% of the total number of households in the country. I was unable to find any justification for the possible savings of £600 /year which seems high when an average annual dual fuel bill is £1,184, in other words the suggestion is that these measures could halve the energy consumption of a property.

The Government intends to consult on whether it is appropriate to end gas grid connections to new homes, in favour of clean energy alternatives. The installation of electric heat pumps is intended to grow from 30,000 per year to 600,000 per year by 2028, and there will be a consultation over new regulations to phase out fossil fuels in off-grid properties, including a backstop date for the use of any remaining fossil fuel heating systems.

This will be a major challenge in rural properties whose electricity supplies may be less reliable. Also, the efficiency of heat pumps declines dramatically with falling temperatures and once temperatures fall more than a couple of degrees below zero, which is normal in a British winter everywhere in the country, they start to consume a lot more electricity in order to provide adequate heating. Forcing households to pay to replace efficient and cheap gas heating with inefficient and expensive electric heating will be politically challenging.

To provide more options, the Government is interested in increasing the amount of biomethane in the gas grid, and exploring the use of hydrogen, as well as looking at the possible wider use of heat networks.

De-carbonising heating, particularly for households, will be a huge challenge, and will involve both disruption and cost. It is probably the main area where the ambition of net-zero by 2050 can be seriously challenged – does replacing gas and even oil for heating generate sufficient societal benefit to justify the costs and disruption it will require?

Power: renewables, CCS and nuclear are key to the Government’s plans

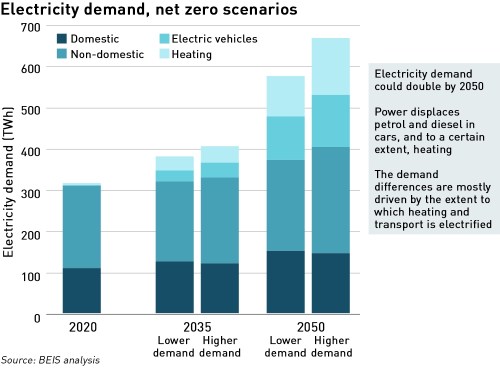

BEIS believes that overall electricity demand could double by 2050, driven by the electrification of heating and transport. In 2050, electricity could provide more than half of final energy demand up from 17% in 2019.

As expected, renewables form a major component of the strategy, with a target of 40 GW of offshore wind by 2030, including 1 GW floating offshore wind. The Government would also like to see at least one power carbon capture and storage (“CCS”) project to be operational by 2030, and believes that gas with CCS will play a key role in the de-carbonisation of the electricity system at low cost (see box on electricity modelling).

As expected, renewables form a major component of the strategy, with a target of 40 GW of offshore wind by 2030, including 1 GW floating offshore wind. The Government would also like to see at least one power carbon capture and storage (“CCS”) project to be operational by 2030, and believes that gas with CCS will play a key role in the de-carbonisation of the electricity system at low cost (see box on electricity modelling).

There is to be a consultation on steps to ensure that new thermal plants can convert to low-carbon alternatives. Since 2009, the Carbon Capture and Readiness requirements have ensured that planning consent is only granted to thermal plants larger than 300 MW for which it will be technically and economically feasible to retrofit CCS. This effectively dis-incentivises the deployment of gas plants above this level, which are typically more efficient, so the consultation will explore the removal of the threshold in light of developments which may allow hydrogen to be a viable alternative clean gas generation technology.

Of course, this all depends on CCS being both technologically feasible and economically viable. In the case of hydrogen, CCS is needed in the production of hydrogen through methane reforming. In the case of gas, CCS must be fitted to the power plant itself. It is not at all clear that gas with CCS is either technically feasible or economic given the significant parasitic load imposed by the carbon capture which will increase the fuel consumption of the CCGT by some 11%. It is much harder to implement than coal with CCS, and so far there are only two commercial power plants fitted with CCS technology, both of which are coal plants, and both of which have been plagued with problems.

By 2022, BEIS will establish the role which BECCS can play as part of a wider biomass strategy (see modelling note).

The other approach is to consider nuclear power, and the Government aims to bring at least one large-scale nuclear project to its Final Investment Decision by the end of this Parliament, subject to “clear value for money and all relevant approvals”. At this point, the project is likely to be Sizewell C, the second EPR being proposed by EDF, but I repeat my view that the Wylfa Newydd ABWR is a better project and should be preferred, not least because (1) EDF’s EPR projects in Europe are all late and over-budget, dramatically so in the case of the flagship Flamanville and Olkiluoto projects, (2) because ABWRs were delivered on time and on budget in Japan before Fukushima, and (3) because technological diversification is desirable and betting our nuclear future on a so-far unproven technology is risky.

The other approach is to consider nuclear power, and the Government aims to bring at least one large-scale nuclear project to its Final Investment Decision by the end of this Parliament, subject to “clear value for money and all relevant approvals”. At this point, the project is likely to be Sizewell C, the second EPR being proposed by EDF, but I repeat my view that the Wylfa Newydd ABWR is a better project and should be preferred, not least because (1) EDF’s EPR projects in Europe are all late and over-budget, dramatically so in the case of the flagship Flamanville and Olkiluoto projects, (2) because ABWRs were delivered on time and on budget in Japan before Fukushima, and (3) because technological diversification is desirable and betting our nuclear future on a so-far unproven technology is risky.

The Government is committing up to £385 million in an Advanced Nuclear Fund aiming to develop a Small Modular Reactors (“SMRs”) by the 2030s and an Advanced Modular Reactor (“AMR”) demonstrator. SMRs and AMRs show significant potential, and could be an alternative to hydrogen in some industrial process. Their modular structure also allows them to be easily tailored to meet local needs.

Somewhat more speculatively, the Government plans to build a commercially viable fusion power plant by 2040, claiming that “the basic science and engineering involved in the production of fusion energy is now well advanced.” This is a bold claim since so far no fusion reactor has managed to produce more power than it consumed. That might change in 2025, when the world’s largest fusion project, ITER in France, is due to be commissioned, but it seems premature to claim that a viable fusion power plant can be delivered in the next 20 years (not least because since the Second World War, nuclear fusion has been “20-years away” – we may still be saying the same 20 years from now).

Flexibility will be a key feature of the future energy system

According to BEIS, “a smarter, more flexible system could unlock savings of up to £12 billion per year by 2050 (2012 prices)”.

The Government intends to support the commercialisation of longer duration energy storage, alongside proven technologies such as lithium ion and pumped hydro storage. Some flexibility solutions could be better delivered through local markets, so a new market framework will be developed which ensures national and local electricity markets are fully co-ordinated and satisfy the full range of system requirements.

“Our current market framework emphasises the cost of fuels such as gas and coal, but renewable technologies, such as wind, do not use fuel at all. It is also poor at valuing some services which will become increasingly important to the system, such as local balancing…We need markets to incentivise both significant levels of new investment and efficient operation, in a system which mixes existing generation with increasing levels of renewables and the flexible technologies which complement them,”

– Energy White Paper

The Government intends to legislate to enable competitive tendering in the building, ownership and operation of the onshore electricity network. This builds on existing models in offshore transmission. The idea is that competitive tendering could be opened up at the distribution level, as well as in the transmission network. This represents a major change to the current industry structure.

The Government intends to legislate to enable competitive tendering in the building, ownership and operation of the onshore electricity network. This builds on existing models in offshore transmission. The idea is that competitive tendering could be opened up at the distribution level, as well as in the transmission network. This represents a major change to the current industry structure.

This year BEIS will also consult more broadly on the way the gas and electricity systems are governed and operated, since the roles of Ofgem, the system/network operators still broadly reflect the industry models from 30 years ago. The long-term role and organisational structure of National Grid ESO will be reviewed and the case for a fully independent system operator may again be made. The industry codes will also be reviewed to ensure that they are fit for purpose going forwards, with consultations taking place this year.

Elsewhere there are plans to support the rollout of charging and associated grid infrastructure along the strategic road network, to support the transition to greater EV use. As part of a £2.8 billion package announced in the 10-point plan, the Government will provide £1.3 billion of funding for EV charging points in homes, workplaces, streets and on motorways across England. There are also plans for at least 18 GW of interconnector capacity by 2030 – a three-fold increase from current levels.

De-carbonising transport will need significant infrastructure and behavioural change

The energy white paper sets out six strategic priorities for transport:

- Incentivising public and active transport

- Explore place-based solutions to local emissions

- De-carbonising the delivery of goods

- De-carbonisation of vehicles

- Making the UK a hub for green transport technology and innovation

- Reducing carbon in a global economy

The UK will end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030, ten years earlier than planned. From 2035, all new cars and vans must be zero emissions at the tailpipe, and between 2030 and 2035, any new cars and vans sold must have significant zero emission capability – the meaning of “significant zero emission capability” will be defined by consultation in 2021. A delivery plan for these phase-out dates will be provided this year, in consultation with stakeholders.

These plans need to be treated with caution. There are real concerns around electric vehicles relating to both the availability of the minerals required for battery production, and the ethics of their extraction. Recent local “green” traffic schemes have proved to be deeply unpopular and are subject to multiple challenges, not least around their impact on disabled people – according to the charity, Scope, there are currently over 14 million disabled people in the UK, or 21% of the population. Of course, not all disabilities relate to mobility, but according to the Government a fifth of disabled people have trouble accessing transport. That figure is likely to rise where so-called “anti-car” or pro-cycling policies are introduced without properly considering the needs of the disabled.

There is also a significant infrastructure challenge. The Government recognises the need for more charging points, and for charging points to have smart capabilities. It is likely that a range of solutions will be needed with some domestic charging capabilities, some local/municipal charging facilities, and then fast-charging stations that are similar to petrol stations, where motorists can take advantage of rapid charging facilities. Local electricity infrastructure is likely to be a limiting factor, as well as the layout of towns and cities where kerb-side access can be restricted.

Entirely new infrastructure will be needed for heavy transport, probably based around hydrogen.

The industrial energy strategy centres on clusters

The white paper accepts that industry will need support with the transition, and it acknowledges that the cost of energy impacts the competitiveness of UK industry more broadly. The Government intends to increase the Industrial Clusters Mission to support the delivery of four low-carbon clusters by 2030 and at least one fully net zero cluster by 2040.

These clusters are areas where related industries have congregated and can therefore benefit from shared clean energy infrastructure. CCS features heavily in these plans although the paper concedes that, “for the majority of industrial sectors, CCUS is not yet a viable investment. The market currently does not provide a sufficiently robust price signal to make industrial carbon capture viable. In addition, low-carbon products do not attract a price premium, making investment harder to justify without a support mechanism.”

In response to these challenges, BEIS is developing a model that will provide revenue support for businesses investing in CCS – a new commercial framework should be finalised by 2022.

A dedicated Hydrogen Strategy will be published early this year which will position the UK as “a world leader in the production and use of clean hydrogen”. The Government wants to see 5 GW of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, with production at scale by the mid-2020s to provide assurance on safety, security, cost and the potential for emissions reduction.

The Government is also planning to implement the world’s first net zero carbon cap and trade market. The UK Emissions Trading Scheme will initially apply to energy-intensive industries, electricity generation and aviation, but there are plans for carbon pricing to be extended across the economy as a whole.

The oil and gas sector has its own section in the white paper, as it is a major employer, supporting around 147,000 jobs across the UK in 2018, which means that the sector is important not just in respect of emissions but also employment. There are two priorities for the sector. The first is to reduce emissions from ongoing operations for example by cutting gas flaring – although the use of hydrocarbons as fuel will be phased out in a net-zero world, oil and gas are important feedstocks in a range of critical industries, meaning that oil and gas production is likely to continue.

The other priority is to re-purpose existing oil and gas infrastructure to support clean energy technologies – as the UK’s oil and gas reserves become increasingly depleted, that infrastructure can be re-used, in CCS and in offshore transmission networks.

The energy white paper is only a baby step – much more is needed

If the Government sticks to its timetable, we should have much more of the detail of how it intends to achieve its net zero ambitions by the end of the year, although the sheer volume of promised publications makes me doubt they will materialise.

But the details of the plans are not the only things that are missing. While the white paper tries to persuade the reader that the energy transition will be positive for the economy, creating new jobs and opportunities for exports, there is no real discussion of the costs.

National Grid has suggested that the cost of the energy transition will be some £3 trillion while the Treasury said in 2019 it would be “in well in excess of a trillion pounds”. Given the extent of the changes that will be required of consumers, it’s time the Government started being transparent about the costs, and if it believes there will be benefits, it should set them out and allow consumers (and taxpayers) to understand the economic trade-offs involved.

This leads to the final gap in all of this which is a wider cost-benefit analysis of the net-zero strategy. The Government should clearly set out the costs to the UK of not fully de-carbonising the economy. The UK’s contribution to global emissions is around 1%. There is a risk that the UK could strive to reach net zero at significant cost to its international competitiveness and at significant harm to vulnerable consumers, while failing to make any material difference to climate change, and that is assuming the climate predictions that are driving policy decisions are correct, when many have not been in the past.

It is also clear that the plan relies heavily on technologies that so far do not exist or are not commercially viable. If we are to believe that the net zero strategy is credible, it needs to be technologically feasible, and include technology milestones and back-up options if a key technology fails to emerge.

Finally, for a target this ambitious there needs to be more joined-up thinking across Government and industry. BEIS, National Grid, the Climate Change Committee and probably the Treasury are all developing plans and models for net zero. A single, robust approach is needed that is capable of accommodating a wide range of different scenarios. And it needs to be open, so that industry participants, academics and other interested parties can interrogate both the model and the assumptions in order to weed out errors and manage groupthink.

There is a very long way to go, and as we move into the third decade of this century, time is running out.

Footnote: A note of caution on the electricity system modelling

The white paper is supported by BEIS’ electricity system modelling. The model seeks to identify low-cost generation mixes that achieve de-carbonisation goals, and is described in this paper. When considering the conclusions of the modelling, it is worth keeping a few things in mind:

- “Low cost” is not defined in absolute terms. For a particular level of demand and technology costs BEIS has identified which deployment mixes can meet a specified carbon intensity. Those deployment mixes are then ranked by their total system cost and the lowest 10th percentile is defined as the “low-cost threshold”. All mixes with system costs below this threshold are deemed “low-cost” solutions. This means there is no link with today’s system costs.

The deployment mixes used are based on what BEIS considers to be “plausible 2050 capacity ranges for those low-carbon technologies that are deployable at scale”. These are: gas with CCUS 2-30 GW, offshore wind 40-120 GW, onshore wind 15-60 GW, solar 15-120 GW, nuclear 5-40 GW. Biomass with CCS (“BECCS”) is not included because the amount of biomass that will be available, and the sector in which it is most efficiently used to meet net zero are both uncertain and under review as part of the work to develop a biomass strategy. This represents a significant difference to the assumptions made by National Grid in its Future Energy Scenarios where BECCS is seen as key to achieving net zero.

The deployment mixes used are based on what BEIS considers to be “plausible 2050 capacity ranges for those low-carbon technologies that are deployable at scale”. These are: gas with CCUS 2-30 GW, offshore wind 40-120 GW, onshore wind 15-60 GW, solar 15-120 GW, nuclear 5-40 GW. Biomass with CCS (“BECCS”) is not included because the amount of biomass that will be available, and the sector in which it is most efficiently used to meet net zero are both uncertain and under review as part of the work to develop a biomass strategy. This represents a significant difference to the assumptions made by National Grid in its Future Energy Scenarios where BECCS is seen as key to achieving net zero.- To take account of uncertainty over technology costs, BEIS constructed cost scenarios based on different combinations of low/central/high capex assumptions for each of the low-carbon technologies, but does not describe what these are in its paper. It assumed that wind and solar costs were correlated while all other costs were uncorrelated. It is likely that these cost scenarios are consistent with BEIS Electricity Generation Costs work which includes the typical assumption of falling wind costs – these assumptions are likely to be unreliable given the work of Professor Gordon Hughes at the University of Edinburgh.

As with all modelling, the outputs are only as good as the inputs. It is important to keep in mind what assumptions have been used, whether they are robust, and what the model is designed to determine. In this case, any discussion of “low-cost” generation mixes must be tempered by an understanding that “low-cost” is purely relative and subject to the biases of the model assumptions; and that those assumptions about the relative cost of different technologies may be unreasonably favouring wind above other technologies.

An extremely revealing article on how complex gaining net zero is. It’s made more complex by politicising the subject, the education / wealth gap in society and the homeownership model. But also what concerns me is that acting alone achieves little. Indeed 1% impact in global emissions. Given we’ve now departed the EU the opportunity to forge a pan EU net zero policy has all but evaporated. Such a coherent policy would have contributed to much greater than the 1%!

Given this complexity, I’m of the opinion that investors and fund managers with green credentials will be driving net zero more successfully than stove pipped government policy makers who are driven by their parties desire to attract more green votes for winning a majority for their next term in office. Just recently Blackrock Investments relinquished holdings in an Australian coal fired power station because of high CO2 emissions. So the sooner financial regulators sort out Environments Social & Governance (ESG) standards the quicker more investors will be comfortable to invest in driving change and advancing net zero globally.

Additionally our UK lack of large tech companies to fuel GDP will hinder the governments ambitions.

Reading between the lines is a very simple conclusion. Ain’t gonna happen. Unaffordable pipe dream. The key issue is which governments are last to go down this appallingly inadvisable renewable root and have enough money to fund the only viable future – massive nuclear rollout.